|

|||||||||||||

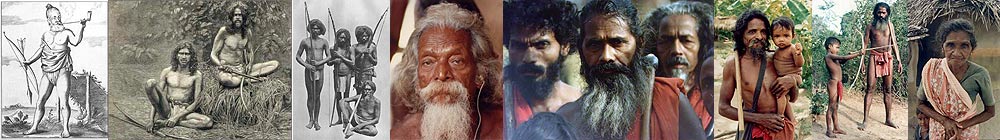

On the Vanished Trails of Coastal VeddahsThe Vakarai Variga Sabhawa brings together coastal and inland indigenous people.Kumudini Hettiarachchi reports

|

|

Dambana Veddahs walk along the Vakarai beach. |

As about 500 Veddahs, with the men in attire varying from loin cloth and bare torso to sarong tucked up and bare torso to trousers and shirt, with bow and arrow or axe slung over the shoulder and women in skirt and blouse, cloth and jacket or saree make themselves comfortable in huts and shelters put up by the 233 Brigade of the Army, the Sunday Times traces the trail that led to the coastal Veddahs. The trail had begun when Dilmah Conservation, as part of its programme to support marginalized communities to attain sustainable livelihoods made contact with the Veddahs.

Being an ancient people, the Veddah community is often considered irrelevant in a 21st Century context. Yet their traditions, culture and history are inextricably a part of who we are today - they define the identity of the Sri Lankan people, says MJF Foundation and Dilmah Conservation Trustee Dilhan Fernando. "Our engagement with the Veddah community has the objective solely of aiding the community to record and preserve their ancient traditions, whilst at the same time integrating themselves socially and economically into the present time," he explains, adding, "In understanding how best we should do this without harming the heritage of the Veddahs, we examined the Australian indigenous community. There were parallels and learnings and therefore we facilitated contact amongst the two."

"Our main emphasis though remains on protecting the uniqueness of the Veddah heritage and drawing lessons from their traditions, their sustainable existence, and helping them in protecting and benefiting from their culture," says Mr. Fernando.

|

|

Coastal Vedda elder, Palchenai

|

|

| Coastal Veddas of Panichankerny speak Tamil yet still cherish their ancestral identity as hunter-gatherers. |

Tasked with collecting all information possible about them, it was Dilmah Conservation Manager Asanka Abayakoon and researcher Nuwan Gankanda who pored over the literature including The Veddas by the Seligmanns published over a century ago, considered the Bible on the Veddahs. To get the numbers they also looked at the censuses of 1921 and 1953.

"In 1921, there had been 2,489 Veddahs in the Batticaloa district and 707 in the Trincomalee district while in 1953 there were only 33 in Batticaloa and none in Trincomalee," says Asanka, pointing out that the Embalawa Veddah tribe mentioned by the Seligmanns had simply vanished.

What had happened, they questioned. Had they been wiped out by disease? Had they died of starvation?

The trek along the eastern coast, from village to village, mentioned in ancient writings as having the 'aborigines' of Sri Lanka began then, first by Nuwan, later joined by Asanka.

Gently asked, the instant response of the inhabitants had been, 'No, we are not Veddahs', but slowly and surely as they dug into the past came murmurings that although the present generation's birth certificates read 'Tamil', their fathers and grandfathers had 'Veddah' on their documents, says Nuwan. That is how Asanka and Nuwan stumbled on the 'Vedars' during their walkabouts.

The Vedars' beliefs and rituals differ from those of the Tamils while they bear a strong resemblance to what the Veddahs follow, points out Asanka, while Nuwan adds that they brand their cattle with the sign of the dunna (bow), used by Veddahs in other areas of the country as well.

Due to their fishing activities, they have been mistakenly branded as sea-going. Isolation from the main clans of Veddahs has been their situation in every sense of the word and some of the findings of Asanka and Nuwan add a quality of mystery to them which needs unravelling without changing their lifestyle.

Some of the Vedars had been built houses with cemented floors and provided basic amenities such as beds by the army after the tsunami, only to find that they were sprinkling sand on the floor for sleeping and using the beds as tables to keep their pots and pans.

Another tale doing the rounds among the Vedars is how two of them from the Lenawa tribe had somehow made their way to the Kataragama festival a long time ago and seen the pageantry there. Having drawn vivid pictures in the minds of their clan members on their return home, the leader had decided to re-enact the ceremony. With no oil for the pandam, they had killed and used the fat of the wild boar which in turn had lured the leopards which preyed on the Vedars, decimating them. The whole village had been wiped out.

|

The Kiri Koraha ritual-invoking the blessings of the spirits of dead relatives. |

Another folktale is that Batticaloa had been known as Puliyankulam, after a Veddah named Puliyam who was living there. Moving away from legends and tales, Asanka suggests that we look closely at the Vedars, pointing out that they look different to the Tamils. With the end of the war, Asanka's and Nuwan's search for the Vedars intensified along the coast from south of Vakarai to north of Trincomalee in villages such as Verugal, Kalkudah, Ilanthurai, Panichchankerni and Mankerni.

Find they did, nearly 20 villages believed to be home to about 30,000 Veddahs going about their livelihood of fishing with del (nets) or in small canoes, climbing high up trees to mee kadanna (collect honey) and growing paddy and vegetables.

It was then that the idea was mooted by the Dilmah Conservation team to turn the spotlight on the coastal Veddahs. They first brought Uruwarige Wannielaththo to the area to introduce him to the Vedars and suggested that the Variga Sabhawa be held on the eastern coast to take the Vedar cause to the people of Sri Lanka.

As darkness envelopes Vakarai and the kurumba lamps (kurumba filled with oil and stuck with a twirled up cloth as the thiraya) glows in the darkness, the different clans begin shanthi karma such as Kiri Koraha, a ritual to invoke the blessings of the spirits of dead relatives, before the much-awaited Variga Sabhawa.

While the women attend to their duties of feeding and looking after the children, the night advances and the Variga Sabhawa is held under Uruwarige Wannielaththo, sans a single woman or outsider, for this important discussion on the issues faced by them as well as their plans for the next year is restricted to male clan leaders.

The next day, Sunday July 31, amidst much Veddah dancing, pomp and pageantry Uruwarige Wannielaththo presents the Variga Sabhawa report to none other than the "Maha Hura" President Mahinda Rajapaksa before hosting him to a sumptuous spread of Veddah food.

Back to their humble homes they went after the meal of kurakan thalapa and rotti, cowpea curry, a mind-blowing green kochchi sambol and mung kevum, washed down with beli-mal and ranawara drinks with licks of kithul jaggery from the upturned palm.

Land and Water, Their Plea

What coastal Veddah leader Nallathambi Velayethan pleads for is what Uruwarige Wannielaththo echoes and has put forward to President Mahinda Rajapaksa. Land and water for cultivation, access to forests to continue their hunter-gatherer lifestyle, are some of the issues that have come to the fore at the Variga Sabhawa, with a matter of grave concern for Uruwarige Wannielaththo being the plight of the widows within their community.

|

Coastal Veddah Leader Velayethan |

Velayethan, 47, from Kunjankalkulam with 60 families, stresses that although there has been a gradual "change in their identity" from Veddi to Tamil over the years, they are very much Vedars. The children's race had been entered on birth certificates as Tamil and they had gone to Tamil schools. With the 30-year conflict, the instincts and knowledge of the area of the Vedars had been exploited by the LTTE in the east, with many being recruited as cadres.

Smiling and handsome Thevanayakam Shankar, 30, who walks among the soldiers with confidence at Vakarai is just one example. Having been coerced into the LTTE as a teenager he had been part of many an operation. With the dawn of peace, Shankar had gone into hiding in the jungles he knew well, but later surrendered in fatigues and all and been in rehabilitation for one year.

Back home in Veragal close to Kalladi with his wife and seven-year-old daughter, now, he engages in catching meen (fish) in the shallow sea with his fibre-canoe. Among the Vedars are believed to be many politicians including Eastern Province Chief Minister Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan (Pillayan).

Courtesy: The Sunday Times of August 07, 2011

Cultural Survival's 1995 survey of east coast Veddas

Sinhala-Tamil Nationalism and Sri Lanka's East Coast Veddas

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |