|

||||||

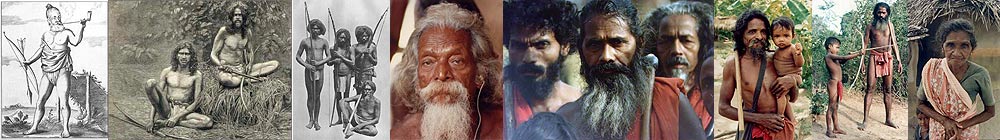

The Veddas of Sri Lankaby Lakshman Indranath KeerthisingheVeddas are the aborigines or indigenous people of Sri Lanka . Mahawansa reveals that Veddas are descended from Prince Vijaya (6th-5th century BC), the founding father of the Sinhala nation, through Kuweni a woman of the indigenous Yakka clan whom he had espoused.

Bori Bori Sellam-Sellam Bedo Wanniya, The Mahavansa relates that following the repudiation of Kuveni by Vijaya, in favour of a 'Kshatriya' princess from the Pandya country, their two children, a boy and a girl, departed to the region of Sumanakuta (Adam's Peak in the Ratnapura District, and their progeny gave rise to the Veddas. Veddas are believed to be identical with the 'Yakkhas' of yore. Veddas are also mentioned in Robert Knox's history of his captivity by the King of Kandy in the 17th century. Knox described them as 'wild men', but also said there was a 'tamer sort,' and that the latter sometimes served in the king's army. Archaeological scholars such as Nandadeva Wijesekera (Veddas in transition 1964) hold the view that the Ratnapura District, which is part of the Sabargamuwa Province, is known to have been inhabited by the Veddas in the distant past. The very name 'Sabaragamuwa' is believed to have meant the village of the Sabaras or 'forest barbarians'. Such place-names as Vedda-gala ('Vedda Rock'), Vedda-ela ('Vedda Canal') and Vedi-kanda ('Vedda Mountain') in the Ratnapura District also bear testimony to this. As observed by Wijesekera, a strong Vedda concentration is discernible in the population of Vedda-gala and its environs. As for the traditional original language of the Veddas, it is presently used primarily by the interior Veddas of Dambana. Communities, such as Coastal Veddas and Anuradhapura Veddas that do not identify themselves strictly as Veddas, also use Vedda language in part for communication during hunting and or for religious chants. Linguists opine that the parent Vedda language(s) is of unknown generic origins, while Sinhalese is of the Indo-Aryan branch of Indo-European languages. Phonologically it is distinguished from Sinhalese by the higher frequency of palatal sounds C and J. Instead of borrowing new words from Sinhalese,the Veddas created a combinations of words from a limited lexical stock. Sinhala speaking Veddas are found primarily in the southeastern part of the country, especially in the vicinity of Bintenne in the Uva District. There are also Sinhala-speaking Veddas who live in the Anuradhapura District in the North Central Province. Another group, often termed East Coast Veddas, is found in coastal areas of the Eastern Province, between Batticaloa and Trincomalee. These Veddas speak Tamil as their mother tongue. One of the most distinctive features of Vedda religion is the worship of dead ancestors: these are termed 'nae yaku' among the Sinhala-speaking Veddas. There are also peculiar deities that are unique to Veddas. One of them is 'Kande Yakka'. Veddas along with the island's Buddhist, and Hindu communities venerate God Skanda or Murugan at the temple situated at Kataragama, showing the coexistence that has evolved over 2,000 years. Kataragama is supposed to be the site at which the God Skanda met and married a local tribal girl, Valli, who in Sri Lanka is believed to have been a Vedda. There are a number of other shrines across the island, not as famous as Kataragama that are as sacred to the Veddas as well as to other communities. Vedda religion centred round a cult of ancestral spirits known as nae yakku,(or relative spirits or demons), whom the Veddas invoked for game and yams. The Vedda marriage ceremony is a very simple affair. The ritual consists of the bride tying a bark rope (diya lanuva) around the waist of the bridegroom. This is the essence of the Vedda marriage and is symbolic of the bride's acceptance of the man as her mate and life partner. Although marriage between cross-cousins was the norm until recently, this has changed significantly, with Vedda women even contracting marriages with their Sinhalese and Moor neighbours. In Vedda society, the woman is in many respects man's equal. She is entitled to similar inheritance. Monogamy is the general rule, though a widow would be frequently married by her husband's brother as a means of support and consolation. Death too is a simple affair without any ostentatious funeral ceremonies and the corpse of the deceased is promptly buried. Although that medical knowledge of the Vedda is limited, it nevertheless appears to be sufficient. For example, pythonesa oil (pimburu tel), a local remedy used for healing wounds, has proven to be very successful in the treatment of fractures and deep cuts. The Veddas believe in the cult of the dead. They worshipped and made incantations to their nae yakka (relative spirit) followed by other customary ritual (called the Kiri Koraha) which is still in vogue among the surviving Gam Veddas of Ratugala, Pollebedda, Dambana and the Henanigala Vedda re-settlement (in Mahaweli systems off Mahiyangane). They believed that the spirit of their dead would haunt them bringing forth diseases and calamity. To appease the dead spirit they invoke the blessings of the nae yakka and other spirits, like Bilinda Yakka, Kande Yakka followed by the dance ritual of the Kiri Koraha. Until fairly recent times, the rainiment of the Veddas was remarkably scanty. In the case of men, it consisted only of a loincloth suspended with a string at the waist, while in the case of women, it was a piece of cloth that extended from the navel to the knees. Today, however, Vedda attire is more covering, men wear a short sarong extending from the waist to the knees, while the women folk clad themselves in a garment similar to the diya-redda (akin to a bikini) which extends from the breast line to the knees.

Vedda cave drawings such as those found at Hamangala provide graphic evidence of the sublime spiritual and artistic vision achieved by the ancestors of today's Wanniyala-Aetto people. Most researchers today agree that the artists most likely were the Wanniyala-Aetto women who spent long hours in these caves waiting for their menfolk's return from the hunt. Understood from this perspective, these cave drawings depict brilliant feats of Wanniyala-Aetto culture as seen through the eyes of its women folk. The simple yet graceful abstract figures are portrayed engaging in feats of vision and daring that place them firmly above even the greatest beasts of their jungle habitat. Veddas were originally hunters and gatherers. They used bows and arrows to hunt game, and also gathered wild plants and honey. Many Veddas also farm, using 'chena' cultivation in Sri Lanka. East Coast Veddas also practice fishing. Veddas are famously known for their rich meat diet. Venison and the flesh of rabbit, turtle, tortoise, monitor lizard, wild boar and the common brown monkey are consumed with much relish. The Veddas kill only for food and do not harm young or pregnant animals. Game is commonly shared amongst the family and clan. Fish are caught by employing fish poisons such as the juice of the pus-vel (Entada scandens) and daluk-kiri (cactus milk). The Veddas' culinary fare is also deserving of a mention. Amongst the best known are gona perume, which is a sort of sausage containing alternate layers of meat and fat, and goya-tel-perume, which is the tail of the monitor lizard (talagoya), stuffed with fat obtained from its sides and roasted in embers. Another Vedda delicacy is dried meat preserve soaked in honey. In the olden days, the Veddas used to preserve such meat in the hollow of a tree, enclosing it with clay. Such succulent meat served as a ready food supply in times of scarcity. The early part of the year (January–February) is considered to be the season of yams and mid-year (June–July) that of fruit and honey, while hunting is availed of throughout the year. Nowadays, more and more Vedda folk have taken to chena (slash and burn) cultivation. Kurakkan (Eleusine coracana) is cultivated very often. Maize, yams, gourds and melons are also cultivated. In the olden days, the dwellings of the Veddas consisted of caves and rock shelters. Today, they live in unpretentious huts of wattle, daub and thatch. Some observers have said Veddas are disappearing and have lamented the decline of their distinct culture. Development, government forest reserve restrictions, and the civil war have disrupted the traditional Vedda ways of life. A renowned anthropologist Dr. Wiveca Stegeborn, has been studying the Vedda since 1977, alleges that their young women are being tricked into accepting contracts to the Middle East as domestic workers when in fact they will be trafficked into prostitution or sold as sex slaves. Vedda populations of this kind are increasing in some districts. Leonard Woolf had written a very popular novel based on the life of Veddas titled Village in the Jungle. Courtesy: The Sunday Leader of December 11, 2011

|