|

||||||

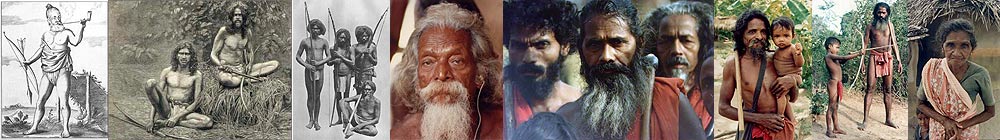

East Coast Veddas: Caught between two worldsBatticaloa's tiny coastal Vedda community is poverty-stricken, malnourished and fading fast

|

|

|

The shaded path suddenly opened up to a micro village, with perhaps less 20 families residing in light blue, partially constructed houses. An old woman, decked in shabby clothes was washing a thin cloth, using water pumped by a tube well nearby. My guide warns me that they do not like to be asked specific questions with regard to their ethnicity and might turn violent if they do not like my line of questioning.

These 'different' people are commonly identified as the 'coastal' or 'Muhudu' Veddas. They are an indigenous community who make their living by fishing, honey gathering and a little bit of agriculture. Today, most of what is remaining of this tribe of East Coast Veddahs have mixed with various races and living in and around the Batticaloa town, especially with Tamils. Some look very much like modern Tamils, with modern dresses and using Tamil as their mother tongue.

|

|

Coastal Vedda elder, Kathiraveli

|

|

| Coastal Veddas of Panichankerny speak Tamil yet still cherish their ancestral identity as hunter-gatherers. |

The people however dislike being identified as hailing from an ancient indigenous tribe, largely due to the prevailing caste hierarchy in the eastern region. The Vedda community is considered the lowest of the regional castes and shunned by persons of higher castes in the region. As a result of denying themselves thus, there has been a tremendous loss of heritage and roots for the coastal Vedda peoples. Tragically, the term veddan which is Tamil for veddha is now used in the region only to rebuke a stubborn or naughty child.

Strangely enough, no matter how often the region of Vakarai and its surroundings have been ravaged by war, the Vedda clans continue to live in the area.

Further along the road that leads to this small habitat, a

Vedda woman was modernly dressed in a t-shirt and skirt and

mending her fishing net. It is likely she received her modern

attire during their displacement due to the tsunami. Walking up

to her, I politely I asked her name and age. She wasn't very

conversant but her old mother walked by and said her name is

Ponnamma and added that she was 40 years old. Instantly, Ponnama

found her voice and said that she's not 40, but also said she

had no idea how old she was.

Ponnamma has eight children and each one is maybe an inch

shorter than the other. Regrettably, they also do not know their

ages and are all clad in rags.

At a house nearby, a small boy named Gajendran lives with his

mother. Wearing a red unbuttoned checked shirt, this boy looked

barely two years old, although his mother tells me he is nine

and currently studies in Grade III of the village school. Many

in his little community laugh that his school bag is bigger than

he is, but Gajendran does not seem to be bothered.

"He got rashes when he was born. That's the only sign I could

relate to his sickness," said his mother, Vasanthi, who looked

like she was in her mid- 20s, although she cannot recall her

proper age. Soon, she went into a room which is dedicated to the

traditional way of cooking fish by the coastal Veddahs. The fish

is caught and placed on a long steel grill to burn on a small

fire.

Moving South of Katheriveli, I was introduced to another set of

Coastal Veddahs in Mankerni, 48km away from Batticaloa town.

Soon I saw an elderly Vedda, 82 year old Byron Ummani, who

warmly welcomed me and asked how he could be of assistance. He

can speak the Vedda tongue, which sounds very similar to the

Sinhalese language. It is also interesting that his first name

denotes a Burgher influence.

"Thaiya nama mokkaddha? What's your name?," is the question

Ummani asked when I entered his house.

"My parents used to talk this language very fluently and it is a

must for the little ones of those days to learn this language if

one is to survive in our clan. But in my time, due to the ethnic

tension, many of our people moved away from our clan and never

came back. Then nobody was willing to talk this language and my

children's generation abandoned it as it was of no use to them

now," he said.

The lives of this community in Mankerni are much better than

those in Kathirveli. Their clothes and houses are clean and tidy

and they welcome strangers without suspicion to their dwellings.

Studies have not been done to establish any difference between

these two Vedda clans though they are closely related to

'coastal Vedda' category. Most importantly, these Mankerni

Veddas knew their ages and articulated a good knowledge of

everything. Maybe, the location had made a difference, as

Mankerni is an area relatively accessible to town and commercial

sites, whereas Kathiraveli is a remote location, accessible by

only a barely motorable road and thoroughly neglected during the

years of war.

Ummani also said they worship a God named 'Upathaiya', whose

image greatly resembles Lord Pillayar, a Hindu deity. "We make

fruits, flowers and other kinds of food items as offerings to

Lord Upathaiya. Then we wrap these offerings in a cloth and

worship it."

During his youthful days, Ummani says he used to go hunting with

his parents and then when restrictions were laid, he fished for

survival and also gathered honey during the season.

His daughter, 39 year old Santhiran Rupavathi, living next door

was putting her pet mongoose in its cage. It is said that most

people in this area tame mongoose to avoid snake bites.

"My children are schooling. We live mostly by fishing and honey gathering during the season. Drinking water is a problem in our area during the dry season," she said, adding hopefully that someone would solve the water problem soon.

These coastal peoples were traditionally forest wardens who protected the jungle which provided their livelihoods. Living in the jungle, they never required the sanitation and other facilities that are part and parcel of modern life. Now living among urbanites, these indigenous tribes still retain parts of their traditional lifestyles. This primitive lifestyle is frowned upon by modern eastern society and they are thus relegated to the lowest caste in the regions they inhabit, because they are caught, cruelly between these two worlds.

An expert view

Dr. Patrick Harrigan is involved in research on Veddas with the Living Heritage Trust that advocates the recognition of Sri Lanka's indigenous people and currently serves as Executive Director of Sri Lanka Children's Trust.

Harrigan says that East Coastal Veddas themselves claim they are aboriginal (adivasi) Veddas (vedar paramparai). For anthropologists, international agencies like the United Nations, and others who study or work with tribal peoples, peoples' own tradition is sufficient evidence in itself. "So, yes, since at least anthropologists C.G. and Brenda Z. Seligmann published their 1911 account of East Coast Veddas, these people have been accepted as Veddas indigenous to Sri Lanka," he says.

According to Harrigan, East Coast Veddas do not claim any relation to the Veddas of Dambana or any other part of the island, nor do Veddas of the interior claim any relation to coastal Veddas. They appear to be distinct tribal groups.

"The term 'Vedda', however, was assigned to all these tribal peoples by immigrant peoples (Sinhalese and Tamils) who arrived much later," says Harrigan.

With regard to how these native people arrived in our country,

Dr. Harrigan explains, "The 'Vedda' peoples or tribes,

including the east coastal Veddas, appear to have arrived in

Sri Lanka during or prior to the last ice age about 6,000 years ago when

the sea levels were low enough that India and Sri Lanka were one

continuous land mass. Veddas have no tradition of having

arrived here by boat, as do the Sinhalese and Tamils and

everyone else but the Veddahs. But the Veddas arrival took

place so long ago that it is only possible to deduce that they

did not sail or swim here, but walked here when India and Śrī

Lanka were one and the same land mass."

Dr. Harrigan sadly notes that once a generation turns its back

on its cultural heritage, the chain is broken forever. This is

the condition very regrettably prevailing the east with regard

to the Vedda community. This led the young generation of East Coastal

Veddas to deny their connection with the past, their group

identity or cultural heritage.

"Today young people especially feel insecure, both economically and in terms of their self identity. They want to dress and speak not as people of their own community, but as outsiders, even as foreigners in their own native land. The antidote, in part, is to give a voice to community elders by giving them access to make their views heard through the printed and electronic media. Also if young people could find decent livelihood opportunities in their home communities, they would not feel so attracted to quit their communities and leave," says Dr. Harrigan.

Courtesy: The Nation of 1 February 2009

Cultural Survival's 1995 survey of east coast Veddas

Sinhala-Tamil Nationalism and Sri Lanka's East Coast Veddas

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |