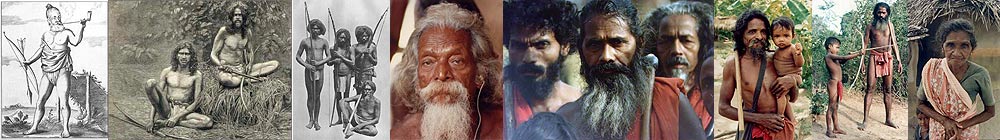

Colonial Histories and Vädda Primitivism

Part Three: The Spread and Dispersal of Vädda Lineages

The Veddah with his axe encounters and defeats bruin. The Graphic, November 26, 1887

|

I now want to demonstrate the presence of Väddas in

virtually every part of the nation after the 16th century during the period of

the Kotte, Kandy and Gampola kings. I will use what I call "intermediate texts," mostly

palm leaf manuscripts from this period written in simple Sinhala by local

intellectuals and sometimes ordinary literate citizens rather than the classic

histories written by monks. I will initially deal with ritual texts from such

post harvest ceremonies like the kohombā kankāriya. Then I

will use the following intermediate texts: kadaim pot or "boundary books"

that demarcate the boundaries of the island and also of regions and districts;35

vamsa kathā especially a short text known as vadi vamsaya

and a much longer one, vanni rajavaliya; then I will sample a

fascinating and enormously prolific genre known as vitti pot, or "stories

about episodes or events;" and finally, I shall briefly refer to a few lekam

miti or land-tenure registers. Especially famous ones like the sabaragamuva

hi lekam mitiya are well-known to scholars though few have used thern.36

Incidentally, all of these intermediate texts give us invaluable information on

the migration of different kinds of people to Sri

Lanka mostly from southern India (not necessarily

Tamil Nadu) but also from Southeast Asia. We are in the process of transcribing a few of these

texts and I will only present a sampling from the ones I am familiar with.

- My first example is a ritual text known as Väddan andagahima, or "roll-call

of the Väddas," sung during the well-known ritual of the kohomba kankariya

which suggests that the Vädda territory was practically coterminous with that

of the Kandyan Sinhalas. In two texts of Väddan andagdhima, one edited

by Charles Godakumbura and the other by Mudiyanse Disanayake, over ninety Vädda

villages are mentioned. The Väddas of Bintanna are not included, presumably

because they were unknown to the composers of these texts.37 No

reference is made to Väddas living in Śrī Lanka's Sabaragamuva province either, which

according to the Mahavamsa account was where Kuveni's children went. Some

of the Vädda areas are familiar to those living in and around the modern city

of Kandy such as Asgiriya, Bogambara and Hantana while others are well known to many of us:

Batalagala, Gomiriya, Maturata, Hunnasgiriya, Lower Dumbara, Kotmale, Nuvara Eliya, Kehelgamuva

and Uragala. Needless to say these are all Sinhala (and estate Tamil) areas

today. These lists are by no means exhaustive: but they are almost always from

the area around Kandy, the North Central Province, the Dumbara and Kotmale valleys and Uva. Lest die-hard

empiricists think that the evidence from the kohombā kankāriya

is of little value I might add that the kingdom of Kandy itself was founded by

Vikramabahu (c. 1474-1511) in what was known as "Katupulle bada Senkandha

naine Srivardhanapura" a high-faluting name for what was earlier called the

village of Katupulla and ruled by a Vädda chief known as Katupulle Vädda. Equally

interesting is the fact that the Kandyan kings had a kind of police force known

as katupulle atto which I am sure was constituted by the Väddas of that

name.38

- My second sampling is from the matale kadaim pota ("the book of boundaries

of the Matale district"), and I will use Abeywardene's edition. For us Matale

would be unthinkable as a habitat for Väddas because its present inhabitants

are mostly Sinhala, followed by later immigrants into the region, Muslims and

estate Tamils. Yet the matale kadaim pota written around the mid 17th

century presents an entirely different picture. In this account the king of

Matale, Vijayapala, the older brother of Rajasinha II, summoned Niyarepola

Alahakon Mohottala, and asked him to name the denizens (lit. men and animals)

of Matale and the reply was: "Lord, there are only three [noble] houses in the

rata of Matale" and when the king asked what these houses were, "Lord, there is

Kulatunga Mudiyanse of Udupihilla, Vanigasekere Mudiyanse of Aluvihara,

Candrasekere Mudiyanse of Dumbukola [Dambullal], [and then also] Gamage Vädda

and Hampat Vädda of Hulangamuva, and when the king asked who are there in the

lands beyond (epita rata), Lord on the other side of the steep waters (hela

kandura) of Biridevela, there is Kannila Vädda guarding (hira kara

hitiya) at Kanangamuva, and Herat Banda guarding at Nikakotuva, and Maha

Tampala Vädda guarding at Palapatvala, Domba Vädda guarding at Dombavela gama,

Valli Vädda (a female?) guarding at Vallivela, Mahakavudalla Vädda guarding at

Kavudupalalla, Naiyiran Vädda [some texts Nayida] guarding at Narangamuva,

Imiya Vädda guarding at Nalanda, Dippitiya Mahage [a female] guarding an area

of nine gavuvas in length and breath in the district known as Nagapattalama,

and Makara Vädda and Konduruva employed in the watch of the boundary (kadaima),

Mahakanda Vädda guarding the Kandapalla [today's Kandapalla korale], Hempiti

Mahage guarding Galevela, Baju Mahage guarding the Udasiya Pattuva of Udugoda

Korale, Minimutu Mahage guarding the [same] Pallesiya Pattuva, Devakirti Mahage

guarding Melpitiya ..."39

The text then goes on to mention that outside of these vädi vasagam

(some versions say väddi vamsa), there are the many Brahmins who

had arrived long ago with the sacred bo tree and are now settled in this district.

Parker mentions a related document from the same period which gives the same list but

adds a few more: The Vädda chief of Hulangomuva, Yahimpat Vädda, and Kadukara

of Bibile (in the Matale district).40 Other versions of this text

also have extra information. These are special lists and do not indicate the

true extent of the Vädda presence in this district because they mention only Väddas

guarding the frontier. We get a glimpse of the larger picture from Archibald

Lawrie's A Gazetteer of the Central Province written in the 1890s.41

He lists about thirty more villages which were Sinhala when he made his

inquiries but, according to local traditions, were once peopled with Väddas. Let

me briefly refer to a few:

- Ambanpola: in Asgiriya Pallesiya Pattuva, Matale South, the name of which is

derived from Ambanpala Vädda. "The inhabitants are descended from Konara Vedda

and Dahaneka Vedda, descendants of Ambanpala."42 Even in Lawrie's

time only the tradition of the founders remained because his notes suggest that

the village was occupied by Kandyan upper castes.43

- Ambitiyava [Embitiyawa]: in Asgiri Udasiya Pattu, Matale South; the vasama

or headrnan's division includes Dorakumbura, Matalepitiya, and Naldeniya

villages. "The tradition is that it derives its name from Embi, a Vedda woman,

who was the first settler."44

- Galagama: Asgiriya Pallesiya Pattuva, Matale South, in Yatavatta vasama.

Lawrie recorded a long and fascinating history, most importantly that the

village was founded by "the daughter of King Wira Parakrama Bahu [c. late 15th

century], of Nevugala Nuwara, alias, Galagama Nuwara, who was married to

a Vedda king of the city of Opaigala."

- Pottota-vela: in Gaugala Udasiya Pattu, Matale East, now a small village of

farmers but which was "first settled by a Vedda named Huwan-kumaraya ["noble

prince"], who covered his house with bark ."45 The name of the

founder suggests a high status Vädda.46

- Puvakpitiya: in Gangala Udasiya Pattu, Matale East, which in Lawrie's time

included Vellalas, aristocratic families and castes of Pannayo, Weavers,

Washers and Smiths. Yet, "the original settler was a Vedda named Hapu

Ratnekala. He first planted arecanut trees [in this area?]."47 The

name of the village Puvakpitiya means "field of arecanut trees."

- Madavala: in Gampahasiya Pattuva, Matale South which has a tradition that "a

Vedda named Herat Bandara formed this village," which once again implies a Vädda

with a Sinhala type name.48

- Udugama: in Gampahasiya pattuva, Matale South. The vasama includes the

following villages: Udugama, Ellepola, Madagama and Golahenvatta. "Herat

Bandara, son of the Vedda King of Opaigala, was the original settler." Thus the

Vädda king's son is a Bandara (a Kandyan aristocrat) and settled in a Sinhala

area; or the Sinhala area was also originally Vädda. In Lawrie's time it was a

multicaste village including Vellalas and Mudaliperuva; perhaps the latter were

descendants of Herat Bandara.49 The royal Väddas of Opaigala are

mentioned in other intermediate texts also.

Finally,

consider that, according to Lawrie, virtually all of Laggala Pallesiya Pattu

consisting of 155 square miles was originally Vädda and especially the villages

of Hanvalla, Kelanvela, Ranamure, Galgedivela, Maraka, Himbiliyakada, Oggomuva,

and Uduvelvela. During the course of my own field work in the late 1950s and

early 60s the tradition was that many of the villages of Laggala Udasiya Pattu

were also once Vädda.

Consider the implications of this information. The Väddas mentioned above have names

which suggest a variety of social backgrounds: you have Väddas that have

lineage names like Gamage associated with members of the ordinary farmer (govigama)

caste in many parts of the Sinhala country. There are names that might well be

unique to Väddas of this region because they are not recognizably Sinhala ones,

for example, Imiya Vädda, Makara, Hampat, Konduruva. One Vädda, Herat Banda,

has a straightforward Sinhala name; and in Lawrie's list there are two Väddas

named Herat Bandara which normally one would think were simply Sinhalas of "good

families." Three Väddas have the word "Maha" or chief or a similar term

attached to their names suggesting persons of great importance, such as Huwan

Kumaraya, "Noble Prince." Then there is Kadukara ("sword-wielding Vädda") of

Bibile whose name suggests expertise in swordsmanship - an interesting finding

because Seligmann says that Väddas simply did not have swords (even though Vädda

derived rituals I have witnessed have sword dances). Most fascinating are the

five Vädda "Mahages", that is, women who are heads of presumably Vädda villages

and also engaged like their male counterparts as guards at watch posts,

contradicting all of the latter day information of Vädda women as shy creatures

kept under strict protection by their men folk. The tradition of female Vädda

chiefs is indirectly confirmed by Lawrie who mentions a Vädda woman Ambi as the

founder of Ambitiyava village. Now for the final thrust: Lawrie refers to a Vädda

King of Opaigala who married the daughter of a Sinhala king, Vira Parakrama

Bahu, a strategic alliance between two kings. His son was significantly named

Herat Bandara in Sinhala style and he founded the village of Udugama and was perhaps

the ancestor of distinguished Kandyan aristocrats, the Udugamas and Ellepolas. It

therefore seems, that as far as the Väddas of Matale are concerned, they were

as internally differentiated as the Sinhalas though they probably did not have

anything approximating the latter's caste system; and some were clearly already

adopting high status Sinhala narnes.50

What about occupational and economic differentiation in Lawrie's list? The term Vädda

comes from vyādha to pierce, that is to hunt, but it is wrong to

think that this was their exclusive occupation. Lawrie provides some hints that

Väddas were also agriculturalists as, for example, the founder of a village who

was the first to cultivate arecanuts. Other reports hint at agriculture as this

note by Lawrie indicates: "The tradition is that a Vedda of Weragama in

Bintenna shot an elk, which after receiving the wound ran as far as the swamp of Iriyagolla and fell down

there. The Vedda followed in the track of the elk and secured it. The Vedda,

seeing the mira was capable of being asweddumized [that is, brought under

cultivation], mentioned it to the King of Sitawaka, who said, 'Thou had'st

better asweddumize and settle there.' He did so."51 Here is a theme I

shall take up later, that of Sinhala kings of this period engaged in opening

lands for agricultural development, in this case aided by a Vädda. I would

think that the Väddas who had Sinhala names like Herat Bandara would have also

practiced agriculture in addition to hunting as much as the Sinhalas of this

area belonging to the farmer caste practised hunting in addition to agriculture

during that very period.

- My third example is from a text known as the väddi vamsaya ("the Vädda

dynasty") and deals with an event in the kingdom of Gampola. The text says that in the Vadipattuva of Migahagoda a

daughter of a Vädda named Nä Hami married Didiya Tulane Mativalagedera

Srimattu. She had ten sons and one daughter, Sangiti. The sons were under the

employ of King Vira Parakkan of Gampola (also known as Kundapola, the latter a

Tamil gotra name, probably a minor raja of Tamil origins living as a Sinhala

king.) The Vädda sons were all employed by the king as warriors. The following

heroic deeds were performed on behalf of the king by these Väddas:

- When the king's elephant went mad and attacked and killed people the king ordered it

to be killed and his tusks brought to him. This was done by the first son, Kala

Hami and the pleased king delimited a special area and gave him the village of Kalalpitiya.

- The second son informed the king of a treasure trove in Kalatota village; the king

gave him Paranavela village in recognition of his services.

- The third son found a picture or statue of a king where there bee hive; he

collected the honey and the picture and was given Daliya village.

- The fourth son Rusi Hami killed a homed sambhur and brought it to the king who gave

him Verigama village.

- The fifth Vilahami informed the king that there was silver in Hindagoda gala and

the king gave him Halanagama.

- The sixth Nimalahami with his sister Sangiti's husband and his brother (that is,

his two massinas) straightened a tree that had fallen across the palace and

they were given Viyangoda.

- While out hunting in the Digana forest the seventh found a rock with a peacock

engraved on it indicating a treasure. The pleased king gave Maha-ala gama.

- Because the king had an enemy known as Nayaka Bandara he ordered his enemy's

head chopped off and brought to him which the eighth son obligingly did and he

was given Galaulla gama.

- The king's dakum pandura (gifts offered to the king by his subjects) 9 was

being stealthily robbed by Kapuru Bandara who rode a mima (or miva,

buffalo). His head was also given to the king by the last two sons Tika Hami

and Bala Hami who were given Galgoda gama.

The details and boundaries or sima of these villages are given. The ten

brothers collectively went to the king with dakum panduru of lots of bolu

mas (the back cut) of several sambhur deer. They said they wanted a palantiya,

that is, a new honorable surname or vāsagama name. The king asked

the king of the Väddas (vaddi rajā) to find ten women from any

group as brides for the ten Väddas. The Vädda king procured for them ten women

with such lineage names as Mudiyanse, Nayide, Rajapaksa, Karasinha, Abeysinha

and lesser vasagamas such as Deva kula, Dura and Sudu Hakuru. These Väddas then

were given a new palantiya name: Pendi Duraya (which nowadays might suggest low

status but certainly was not the case in Kandyan times). I leave you to assess

the significance of this text but it does indicate I think a process where one Vädda

family breaks away from a larger lineage and is given a new name and caste

status. Vädi vamsaya illustrates another feature of these types

of texts: the focus is on some special service performed for the king but this

ignores the larger context. More likely these were warriors in the service of

the king and the titles and honors recognize this fact but the literary

convention is to mention one outstanding act only.

- The fourth example is from the vanniye kadaim pota ("the boundary book for

the Vanni"), the disputed area very much in the news today. It deals with an

event (vitti) in the life of Panikki Vädda, an elephant catcher for King

Bhuveneka Bahu of Sitavaka (circa mid 1511 century), and living in Eriyava,

near Galgamuva in the Kurunagala district. He was obviously an important person

for his adventures are repeated in four other intermediate texts, including the

vanni rājāvaliya and a verse ballad. When Panikki Vädda

captured a tusker for the king, the latter granted him lordship of the four

Vanni districts or pattus, namely, Puttalam Pattu, Munessaram Pattu,

Demala Pattu, and the Wanni Hat Pattu, and honored him with the title "Bandara

Mudiyanse."52 One of his assistants is named as Dippitigama Liyana Vädda

Lekam (also known as Nikapitigama Liyana Vädda) no doubt a scribe who was part

of this chief's entourage. Other texts indicate that the latter was granted the

chieftain-ship when Panikki Vädda died. Panikki Vädda had twelve chiefs under

his command called panikki rālas and this text, as well as another vitti

pota, gives a list of these panikki rālas, the soldiers in

their command (which numerically were not many) and detailed descriptions of

the lands they were given for services rendered to the king. As with the Matale

Väddas these villages are now Kandyan Sinhalas. It can be assumed that the

descendants of these distinguished Väddas became Bandara Väddas and then merged

with the Sinhala Bandara aristocracy. Panikki Vädda himself was deified at his

death and he is still propitiated in rituals over a vast area of Bintanna-

Vellassa that I am familiar with from my fieldwork.

- I will briefly draw your attention to the final example from land-tenure

registers or lekam miti. I haven't begun to study these yet in any

detail but I have read two texts of these land tenure registers from Pata and

Uda Dumbara from 1798 and 1819. These give lists of families of Väddas living

in this region with documentation of the nature of their houses, the lands they

cultivate, the cattle they own and the names of members of their families. In

Udispattuva, also in Dumbara, there are references to 36 families of Väddas

living in nine villages, presumably alongside Sinhala castes. Similar lekam

miti for Maturata korale mentions 25 families of dada vadi durayi

("hunter-Väddas of the dura caste[?]". I doubt that it is possible to

identify any of these families as Vädda today.

I want to make it clear that the Väddas were everywhere in this island, and not

only in the places listed by me earlier. Thus the Parevi Sandesaya

written in the mid-15th century refers to daughters of Väddas in the area below

the Sumanakuta Peak (Samanalakanda, Śrī Pada) where, according to the Vijaya

myth, the son and daughter of Kuveni originally settled down.53 This

is in the present-day Sabaragamuva province; the etymology of that word means "the

country of the sabaras" or "hunters" and identical with the etymology of

Vädda. It is therefore not surprising to find plenty of references to place names

in Sabaragamuva that indicate previous Vädda presence: väddi pangu

("Vädda land share"), väddi kumbura ("Vädda rice fields"), vädivatta

("Vädda gardens") and väddāgala ("Vädda rock") where a

Sinhala village is now located. The Paravi Sandesaya also mentions

groups of Vädda men and women in the area south of Colombo, around Potupitiya

and Kalutara.54 There were a lot more in this same general area as

late as 1805 because one British observer reported having seen "[Vädda] tribes

who inhabit the west and southwest quarters of the island between Adam's Peak

and the Raygam and Pasdan cories [korales] ... and are much less wild

and ferocious than those who live in the forests of Bintan."55 One

of the most interesting place names on the border of Sabaragamuva and the

Southern Province ("Ruhuna" in the old political geography) is known as habarakada,

"the gateway of the sabaras (hunters)." In the 1960s, when I did

fieldwork in this area, the tradition was strong that this was where Väddas and

Sinhalas met to barter and trade. I also have ritual texts that postdated the

15th century which say that it is a bad omen if you see a Vädda coming from the

direction of Ruhuna, the southernmost province of Sri Lanka. Finally, the evidence of the Seligmanns and more recently

the work by Jon Dart suggest that Tamil-speaking Väddas were found in parts of

the Vanni and the Northern Province, a presence marked in some Dutch maps of Sri Lanka.56

End Notes

- The pioneer work on kadaim pot was done by H.A.P.

Abeyawardana, Kadaim-pot vimarsanaya, Colombo: Ministry of Cultural Affairs, 1978, pp.223-31, my

translation.

- Though scholars writing in English and professional

historians have neglected these "intermediate text' they have been sometimes

taken seriously by scholars writing in Sinhala, the most notable example being

P M P Abhayasinha, Udarata Vitti.

- Charles Godakumbure, Kohombakankariya [Sinhala],

Colombo: Government Press,1963, pp. 90-91; Mudiyanse Dissanayake, "AVädda

connection seen in the dance traditions of upcountry [Kandyan] rituals"

[Sinhala] in, Cyril C Perera, Gunasena Vitana and Ratnasiri Arungalia, eds., A

Critical Review of the Work of A V Suraveera, Colombo: S Godage, ? pp.414-36;

and also a discerning study by the same author, Kohomba Yak Kankariya saha

Samajaya, [Kohomba Demon Ritual and Society], Kelaniya: Shila Printing

Works, 1988.

- Nihal Karunaratna, Kandy Past and Present, Colombo: Ministry of

Cultural Affairs, 1999, p.6. See P M P Abhayasinha, Udarata Vitti, Colombo: M D Gunasena,

1998, p.64

- H.A.P. Abeyawardana, Kadaim-pot vimarsanaya, Colombo: Ministry of

Cultural Affairs, 1978, pp.223-31, my translation.

- H. Parker, Ancient Ceylon, pp.101-02.

- Archibald Campbell Lawrie, A Gazetteer of the Central Province of Ceylon (excluding

Walapane), (Colombo: Government Printer,

1896)

- Ibid., p.39.

- A.C. Lawrie has reference to Ambanpola Nilame who

married into the Talgahagoda family of aristocrats. Ambanpola Nilame himself

must have been a descendant of Ambanpola Vädda, see reference to Talgahagoda,

in Vol. 2, p.810.

- Ibid., p.224.

- I suspect that normal houses in this area were wattle

and daub and covered with straw or grasses (iluk). However, bark houses

were common in Vädda territory of Vellassa and Bintanne at one time; perhaps Huvan-kumaraya had a

regular adobe house but roofed it in the Vädda style with bark.

- A.C. Lawrie, Gazetteer, p.744.

- Ibid., p.752.

- Ibid., p.515.

- Ibid., p.852.

- A neat example of this shift comes from the Matale

Kadaimpota which refers to Kulatunga Mudiyanse of Udupihilla. Udupihilla,

now practically a suburb of the town of Matale, was founded by Väddas and the

present farmer castes are their descendants, according to Lawrie, vol., 2,

p.858. It seems likely that Kulatunga Mudiyanse of Udupihilia, a Sinhala

aristocrat, is a descendant of Väddas.

- Ibid., p.947.

- I am using Henry Parker's translation of this text in Ancient

Ceylon, pp.101-02; see also Abeyawardana, Kadaim-pot vimarsanaya,

pp.21-22.

- Gananath Obeyesekere, The Cult of the Goddess Pattini,

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984, p.304; for other references see, pp.310-06.

- See, K.N.O. Dharmadasa, "Veddas in the history of Sri Lanka," in Vanishing

Aborigines, p.43.

- Robert Percival, An Account of the Island of Ceylon,

London: C and R Baldwin, 1805, p.284, cited in James Brow, Vedda Villages,

p.13.

- I refer to a map in my possession which was originally

published in 1722 by Guillaume de L'Isle (or Delisle), the younger, who was a

member of the Academic Royal des Sciences; it was reissued by the Dutch map

company of Johannes Covens and Cornelius Mortier (1721-78). The area marked in

this map is just north of Trincomalee and up to the eastern tip of the Jaffna peninsula and

referred to as "pays de Bedas;" west of this region is the "pays de Vannias -

Malabares." I assume other maps have this feature also.

|