|

||||

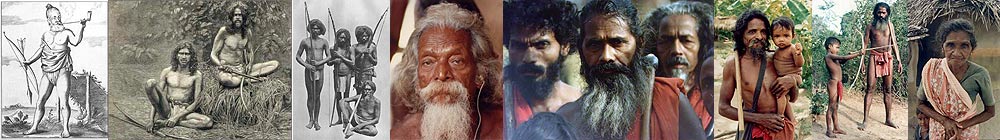

Wanniyalaeto Non-violent Resistance

The old Wanniyalaeto chieftain Uru Warige Tissagami (popularly known as Tissashamy) and his kinsfolk of Kotabakinni, however, refused to be evicted from the land of their ancestors. Officials considered him to be very obstinate and stubborn, for he would not budge an inch no matter how many emissaries came to "talk sense" to him. Finally the government had to concede that these seven families could remain as long as the old man lives. However, according to the 1987 Master Plan for Maduru Oya National Park, the day that aged chief Tissahamy expires, the rest his kinsfolk will have to evacuate the hamlet immediately.7 Knowing this, Tissahamy even refused to die (note: Tissahamy finally expired on 29 May 1998 at the reputed age of 104). Wanniyalaeto leaders allege that since 1974 they have listened to official assurances that a sanctuary of l,800-acre extent will be created for them to pursue their traditional way of life. Successive governments have repeated this pledge, but to date still no government has implemented its pledge. Even this modest figure (amounting to only one percent of the park's area) was originally cited not as a sanctuary for all affected Wanniyalaeto, but only as a buffer zone to prohibit commercial logging activities around Tissahamy's hamlet of Kotabakinni only. In fact, the other affected hamlets cannot possibly be included in a sanctuary of this size, which is sufficient to sustain a few families by their traditional means of livelihood. But the l8OO-acre figure has remained to be seized upon by officials and even, years later, by Tissahamy's attorney, resulting in further tensions and misunderstandings. However disadvantaged the island's indigenous forest-dwellers may appear to be in the eyes of modern-educated observers, nevertheless their sense of honour, justice, and fair play is very keen. Despite centuries of injustice and exploitation by economic predators from outside communities, even to this day the Wanniyalaeto people remain so gentle and patient towards younger cultures that, although they are proficient hunters, they have never been known to raise a weapon in anger, to commit theft or fraud out of greed, or even to raise their voice toward outsiders, let alone to speak any untruth for personal gain. Indeed, these are precisely the elements of their cultural heritage that the Wanniyalaeto are most anxious to preserve for future generations. Colonised Wanniyalaeto are deeply dismayed by the corruption of their culture caused by forced assimilation into a modern society which they regard, justifiably, with utter contempt. |

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |