|

||||||

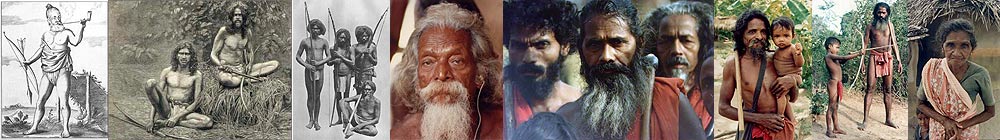

Into The Jungle With Sri Lanka’s Last Hunter-GatherersA trip into the jungle with members of one of Sri Lanka’s oldest tribes reveals a way of life both richly entwined with nature, yet ever more precarious.

by Tom SykesOver two thousand years ago, a lion made love to a beautiful woman in India, and their son, Sinhabahu, was born with lion paws for hands and feet. Sinhabahu in turn had a son called Vijaya, who became the first, legendary king of Sri Lanka (the people call themselves Sinhalase—meaning ‘lion people’) after he and 700 followers arrived on the tropical island, off India’s South East coast, some time around 500 BC. In remote corners of the country to this day the men and women who believe that they are Vijaya’s direct descendants (although anthropologists believe they have been there since at least 5,000 BC), the Vedda—Sri Lanka’s last surviving hunter gatherers—eke out an existence collecting honey, trapping bush meat, and taking the occasional tourist for a trek in the forest. In the National Park of Gal Oya, in the South East of the island, ‘occasional’ is the operative word. Tourists are still thin on the ground up here. The fact that this area was one of the hotspots during the civil war against the Tamil Tigers (which only ended in 2009) and bad roads (in the process of being upgraded now peace has come) keep all but the most intrepid away, for now. After seven hours of driving from the town of Galle, I asked my driver if it was true that only very few travellers made it up here. "Yes, if by few, you mean none," he replied with a chuckle. It’s certainly a major effort to get this far off the beaten track in Sri Lanka, but, for this very reason, Gal Oya is the place where Vedda life continues in its most unadulterated form. And when you find yourself on a honey raid with a Vedda elder in the jungle, you can’t help reflecting it is well worth the trouble of getting there. Thus it was that I watched in amazement as Jaya (or Danigal MahaBandarlage Suda Jayawardane to give him his full name), a Vedda man who thought he might be about 60 but wasn’t too sure, shimmied up one tree with the alacrity of a boy quarter his age. Then, by use of an ingenious giant wooden hook which we had watched him constructing a few minutes earlier (using vines to tie together some rapidly chopped-down lengths of wood), he transferred himself to the adjacent tree, climbing up it until he was over 100 foot in the air. Collecting wild honey is a dangerous occupation—one of the Vedda was killed doing just this three years ago—but it can’t be given up. Honey is the beating heart of the Vedda way of life. The men even showed me an ancient food store: a deep square hole laboriously cut in the rock, into which dried meat was preserved in vast quantities of honey in former times. When the Vedda stop collecting wild honey—it tastes quite unlike normal honey; strong, musky almost, and laced with lumps of wax—then the Vedda way of life will truly have vanished. Jaya who, like all the Vedda, is only about five feet tall, wedged himself in the V formed by two forking branches, about two foot away from a large opening in the tree, which, even from way down below, we could see was thick with ominous, buzzing beasts. Several of the insects seemed to be taking an unseemly interest in our friend’s long grey beard. "Bees?" I asked the Chief. "Bumbola," he said, using the Sinhalese word for hornets. "You eat hornet honey?" Well, no. Hornet honey, it turns out, is the cheap white wine of the Vedda world—not great on its own, but perfectly serviceable for cooking with. The chief (sensibly staying on ground level, I noticed) produced a box of matches and lit a bunch of mixed dry and green leaves which were then hauled aloft using a vine rope by Jaya. He would usually use a rock to create a spark but, he explained apologetically, it takes three days to dry out the cotton ball-like plant matter they use for tinder. Coughing and spluttering, Jaya began waving the bunch of leaves around the nest. The burning bunch was now producing a prodigious amount of thick white smoke. Then, quite unexpectedly, he began to sing in the ancient Vedda tongue—the honey poem, as our guide explained. His voice rang out across the jungle, sounding for all the world like a mournful, musical prayer. It was deeply moving. After about ten minutes of this he reached into the nest—despite the fact that from where we were standing there seemed to be a worrying amount of hornets still buzzing around, but emerged empty handed. No honey. I was gutted for him. His friends on the ground were less sympathetic. They all cracked up laughing. To be fair, Jaya had warned us that we were here at the wrong time of year to collect honey, but had sportingly agreed to thrust his hand into the hornet’s nest anyway. June, he told us, is when it all happens honey-wise. In June, the Vedda men of Gal Oya leave their village, and head into the jungle for up to two months at a time on the great honey hunt. (The village is a rather depressing concrete-block affair into which they were resettled when the caves in which they had dwelt for millennia were flooded in 1952 to create the largest reservoir in Sri Lanka, which now forms the heart of the pristine Gal Oya National Park.) On their journey, they take some rice, chilli and salt. Everything else they catch or collect as they need it. Jaya invited me to come back in June and go honey collecting with them. For two months. I tried to explain about jobs and the time-is-money concept, and Jaya just laughed in mystification, popping into his mouth a fresh hunk of betel nut, the stimulating kernel the Vedda chew all day with tobacco, which produces seemingly endless jets of pink saliva and pink teeth. Even though I won’t be making the two month trek, walking through the forest even for a day with Jaya and the chief was an eye-opening experience. Every plant seemed to be used for something; this one for healing a broken arm, that for extracting the venom from a snakebite, another for sucking the oxygen out of a pond so the fish floated to the top. They can make countless varieties of string from different plants, vines, barks and leaves, and even boasted that one plaited plant fibre was so strong it could be used "to tow a vehicle" as translated by our guide. They would frequently stop and pick berries—rather scary bright red-coloured berries on one occasion—and insist I eat them. I can’t say they were uniformly delicious, but I have no doubt their anti-oxidant properties would have the nutritionists of certain western cities in paroxysms of delight. Although the Vedda have friends in high places—the chief’s government-built concrete-block house is adorned with photographs of his many meetings with the former president—they are in trouble. Few of the younger generation are interested in continuing on with the hardships of the hunter-gatherer way of life, and even among the older men the traditions are fast disappearing. They have been doing so ever since the Vedda here were moved out of the caves in which they dwelt for millennia until the flooding of the valley in 1952. For instance, instead of the traditional loincloths which were made out of softened tree bark, the Vedda now wear mass produced fabric dhotis (rectangular pieces of cloth knotted around the waist) and towels over their shoulders. They do, however, still go barefoot and proudly carry their traditional axes over their shoulders, clamped in place by a cocked head, giving them the appearance of a secretary before the invention of headsets. Hunting with bow and arrow has gone the way of the dodo, although, while on another trek in the forest with a guide provided by the lodge, we did come across a recently baited traditional Vedda dead weight trap, and a pile of picked-clean monkey bones nearby. I am quite sure that given the choice between living in a cave or a breeze-block hut with electricity, a TV and a satellite phone I would choose the easier, drier, safer way of life too, but it was noticeable how depressed the men seemed in the village, and how energised they were out in the jungle. Back in the village, before we set off, they had been adamant that modern huts with proper roofs and electric light were better than caves. But out in the jungle, flushed from the thrill of the honey hunt, when I asked them if they would rather actually still be living this way, climbing trees, collecting wild honey, trapping deer—there was a nod, accompanied by a shy, sad smile which seemed to say that they also knew how impossible that would now be. Courtesy: The Daily Beast of January 31st 2015 |

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |