|

|||||||||||||||

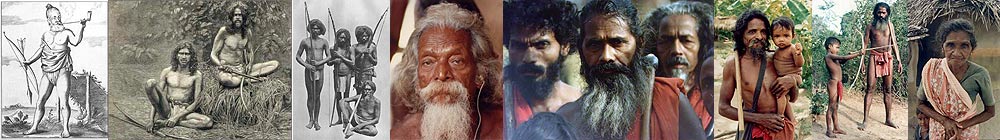

Anthropology Group Takes Activist Stand to Protect Vedda Cultureby Daniel Coleman

|

|

| Above: Many Veddah elders, such as Kiri Banda of Dambana, are keen to preserve the age-old Veddah way of life for generations to come. |

At the stroke of midnight on November 10, 1983, the creation of a new national park in Sri Lanka made cultural orphans of the Wanniya-laeto, the last remnant of a people who appear to have lived on the island for 28,000 years. The final fringe of the forests in which they had been hunters and gatherers was put off limits for all hunting and gathering of food. A Wanniya-laeto who tried to stick to the old ways would be arrested as a poacher.

Since then, the Wanniya-laeto, split into three groups, have been struggling to preserve their culture. And earlier this year the American Anthropological Association, the discipline's largest and most prestigious professional group, took a small step to aid the Wanniya-laeto, but a big step for anthropology. It sent a letter to the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, to protest the treatment of the Wanniya-laeto people, and to ask that they be allowed to live once again on park lands or have access to them.

|

|

Traditional Wanniya-laeto hamlets in Sri Lanka. Map at quarter scale. Click on map to view at 100% scale.

|

That was the first formal action by a Committee for Human Rights established by the association last October in a step designed to move anthropology as a profession to an activist stance taken only erratically in the past, and usually by individual anthropologists. The letter marked the first time the anthropological association itself has actively intervened in a dispute, although it has taken political positions in the past. The association includes both cultural anthropologists, who study cultural groups of people, and physical anthropologists, who study the physical characteristics of humans and their ancestors.

The mandate of the rights committee is broad, said its chairman, Dr. Tom Greaves, an anthropologist at Bucknell University. "While our interventions frequently reflect our concern for the welfare of the isolated peoples who have so often hosted our research," Dr. Greaves said, "our concern is with any group or persons where assaults on their cultural ways have put them in danger."

In addition to the plight of the dispossessed Wanniya-laeto, who can no longer continue their traditional ways as forest-dwellers, the association has now taken up the causes of other cultures as well, lodging complaints with governments and other official groups, like the World Bank. It has protested the mistreatment and displacement of Maya Indians by the Guatemalan Army, the execution of leaders of the Ogoni tribe by the Nigerian Government and the seizing of the lands of the Yanomami Indians in Brazil and Venezuela by gold miners.

Last month, Dr. Yolanda T. Moses, the president of the association, issued a report protesting a January decree by President Fernando Henrique Cardoso of Brazil that reopens to land claims the protected reserves of an estimated 344 tribal societies in the Amazon basin. Dr. Moses sent letters of protest to Mr. Cardoso, the president of the World Bank and the leaders of countries that lend money to Brazil.

One reason for the new activism is concern over the disappearance of cultures, a problem that appears to have become more serious in the last century or two.

While no one can say with exact certainty at what rate cultures are becoming extinct worldwide, Dr. Patrick Morris, an anthropologist at the University of Washington, said, "At least a third of the world's inventory of human cultures have disappeared completely since 1500 -- their languages, their traditions and ways of life, their world view and very identity."

The peoples most at risk are those who are indigenous, the original inhabitants of a land. Often in the areas where they live, biological diversity, the wide range of plant and animal species, is threatened as well.

Dr. David Maybury-Lewis, an anthropologist at Harvard University, said: "The roughly 5 percent of the world population who are indigenous people are being seriously threatened worldwide. Cultural diversity is an important world resource, as essential to the resilience of the human race in the long run as is biological diversity."

Dr. Maybury-Lewis is a founder of Cultural Survival, a group based in Cambridge, Mass., that has labored to protect threatened cultures since its founding in 1972. Its projects include schools of Tibetan language and culture in Tibet and weaving cooperatives in Chiapas, Mexico. Cultural Survival, while numbering anthropologists among its members, is not a professional organization like the anthropological association.

The move to activism by the anthropologists has ignited a debate within the field, with some protesting that such advocacy blurs the discipline's objectivity, or can be perceived as doing so. Others argue that anthropologists have both a moral and professional obligation to protect the people who make the discipline possible by opening their way of life to study.

"When you live for months in a community," said Dr. Greaves, "when the success of your field work depends on the generosity and patience of people who probably didn't invite you but who took you in anyway, a bond of friendship and mutual obligation results. When they encounter abuse, we feel a need to act."

|

| Photo: A Wanniya-laeto tribesman tightens his bow string in his village, Dambana, Sri Lanka; about 2,000 members of his tribe remain. Photo courtesy: The Psychedelic Illusionist |

|

| Contrary to popular notions, Wanniyal-aetto people are bright, intelligent and happy when left to live according to their tradition ways. Wanniyal-aetto children of Hennanigala. Photo by 1992 Patrick Harrigan |

Other anthropologists worry that mixing moral or political concerns with their professional work will dilute their ability to do good science. Dr. Roy D'Andrade, an anthropologist at the University of California at San Diego, said in a letter to The Anthropology Newsletter that "our moral models about the anthropologist's responsibilities should be kept separate from our models about the world," adding, "Otherwise the result will be very bad science and very confused morality."

On a more practical level, some anthropologists have expressed concern that activism will displease some governments and lead them to deny anthropologists access to the people they wish to study -- or take even more severe steps. "Anthropologists have given their lives in Ethiopia, Guatemala and South Africa," Dr. Morris said, "to protect people they worked with."

Cultural anthropology has been challenged before -- in fact, almost from its inception -- as lacking scientific objectivity. Margaret Mead, one of the discipline's stellar practitioners, has been accused of using her data on the Samoans to argue for more liberal sexual standards in America. In the field's early years, anthropologists were accused of being pawns who helped colonial powers control indigenous peoples.

|

|

Mahaweli Development Scheme resettlement areas. Maps at quarter scale. Click on maps to view at 100% scale.

|

|

|

Wanniya-laeto hamlets in Maduru Oya National Park.

|

And, on occasion, the association has taken activist stands. In the 1930's, it issued a statement against Nazi racial theories. In 1991, it spoke up for the Yanomami Indians in Brazil when their tribal lands were being overrun by thousands of miners because of a gold rush in the Amazon basin.

A politically active approach can backfire. In 1991, a Canadian judge ruled against a land claim by the Gitskan and Wet'suwet'en tribes, supported by testimony by three anthropologists. The judge rejected the anthropologists' testimony, saying they were playing a partisan role rather than giving a reliable, impartial presentation of data.

In disregarding the anthropologists' testimony, the judge cited an article of the Principles of Professional Responsibility of the anthropological association, part of which reads: "In research, an anthropologist's paramount responsibility is to those he studies. When there is a conflict of interest, these individuals must come first."

That principle, which was formalized in 1968, has led to what some anthropologists say amounts to a generational schism within the profession. Many anthropologists trained in the 1970's and 1980's were taught that their profession demanded an activist stand.

"I teach anthropologists in training," Dr. Turner said, "that people have a right to their culture and that human rights concerns are inextricably bound up with being an anthropologist." But among those trained in earlier eras, more view their discipline as a pristinely scientific endeavor and see any activism on behalf of the people they study as something that is to be done independently of their professional work, if at all.

Dr. Greaves said, "Those who oppose anthropologists taking these stands argue that we're scientists, not activists."

The case of the Wanniya-laeto people in Sri Lanka

Younger anthropologists are often in the lead in speaking up for threatened peoples. The case of the Wanniya-laeto people in Sri Lanka, for example, is being championed by Wiveca Stegeborn, a graduate student at Syracuse University.

The Wanniya-laeto, known more widely as the Veddahs, have inhabited Sri Lanka for more than 28,000 years, according to archeological evidence. They now number just over 2,000 people.

"Originally, they were all over the island, until the Sinhalese came 2,500 years ago," Ms. Stegeborn said. "Over the centuries, they've gradually retreated and retreated, until now they have no place to go except this last patch of jungle that's now been taken away from them in the name of making it a game park."

Ms. Stegeborn added: "In the years since they were forced from the jungle, they've been split up into several farflung villages, where it's harder and harder to follow their traditional ways. They've always lived off the jungle; now they end up on welfare or do the most menial labor."

Because of Ms. Stegeborn's efforts, the cause of the Winniya-laeto was the first to be backed officially by the new rights committee. The association's letter objecting to the resettlement of the Wanniya-laeto contends that the action violated international law, and it requested that the Sri Lankan Government take remedial action.

"I absolutely believe anthropologists have to take a stand on these disappearing people," Ms. Stegeborn said, "and do something about saving what's left. Otherwise, it's like a surgeon simply watching a patient die and making clinical observations about the fading pulse without trying to save him."

Courtesy: The New York Times of March 19, 1996

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |