|

||||||||||

Guardians of the Red EarthAn American anthropologist among the Danigala Veddasby Jill Priest, (Oregon State University, USA)

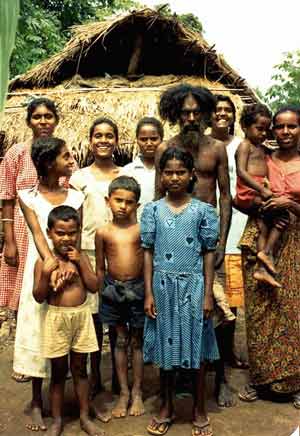

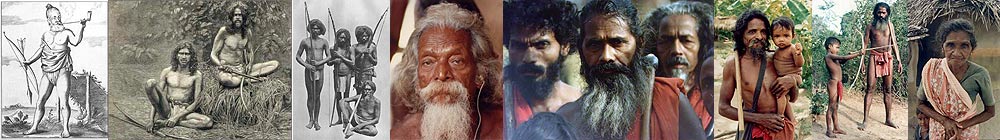

As an American anthropology student conducting her first real field research, I was filled with excitement one day in June 2003 as my vehicle wound its way along the winding jungle road leading from Bibile to Ratugala. Already my guide-interpreter Aruna Suraweera and I had seen poisonous snakes and giant spiders crossing our path, and a majestic elephant had actually stood in the middle of the road and blocked our way. There really is little one can do when an elephant is blocking the road except to wait until he decides he does not want to be there anymore. It gave me an opportunity to take in all the beautiful scenery, the scenery that is the home to the Danigala Veddas. The Danigala Veddas share a common heritage with all Veddas in Sri Lanka. When Prince Vijaya came to the island from India, he began to massacre the inhabitants. Many escaped to caves within the forests and became known as the Wanniya-laeto, which translates to "forest dwellers." Today, they are often referred to as Veddas. As different group dispersed through the forests, the Veddas developed different communities throughout the country.

The Danigala Veddas were one of the groups who escaped into the caves of the jungle. In the 1940s, the government removed them from the Danigala caves and mandated that they live in homes in the forest made with mud walls and thatched roofs. With little option, the Veddas complied and have lived in these designated areas for over fifty years. With their relocation, they separated into two communities. One group moved to the region near Ratugala, and another group relocated to Pollebedda. Few people remain from that time, but the chief of the Ratugala region, Danigala Maha Bandarelage Randunu Wanniya, is still alive to recall memories of his ancestors. According to the Danigala Chief Maha Bandaralage Randunu Wanniya, the original territory of the Danigala Veddas extends from the mouth of Rambakan Oya south to the Gala Oya, which makes up the southern periphery of their land. Their traditional land stretches east to what was formally the bloc Gal Wela and surrounding grasslands, now the Senanayaka Samudraya Reservoir. The northern boundary is set by Ratugala and Makare Mountain. When asked about the relationship to the Danigala land, the Chief says, "I was born on it. This is my people's land because we were born on it." He states that he and his people act as protectors of the land, animals and plant life, especially those that are edible or used in herbal remedies. Their relationship with the land has diminished as the Government has reduced the amount of land to which they have access. Laws now prohibit many of their traditional agriculture practices as well as their right to hunt. When questioned about his thoughts on no longer being able to hunt, the Chief exasperatingly responded, "I don't even want to think about it. I don't even want to think about Government restrictions." He added that he did have fond memories of hunting and still owned the bow and arrow he inherited from his father. The bow and arrow had great cultural significance to the Veddas. These arms represented the ability to obtain food for one's family. With each hunt, they obtained power for future hunts. The arrow also held another type of significance. Traditionally, when a man wished to take a woman as his wife, he would put his arrow into the ground next to the cave of the woman he wished to marry. He would return the next day and ask her to touch the end of the arrow. Once she did this, they would be considered married and would go to the forest together for a few days to consummate their marriage. Once they returned, they moved into a cave together. This method of proposal has become obsolete as men no longer carry arrows. Many members of the community express sadness at the disappearance of the tradition and attribute it to the fact that men cannot hunt and have no need for arrows. Today, men simply ask the woman's parents if he may take their daughter as a wife. If they accept, the couple will move in together, usually on the property of the female's family. However, it is not uncommon to live with the male's family. There is neither a formal ceremony nor a legal contract involved in their marriage customs. Cohabitation and procreation is the symbol of their bond. In general, the Veddas do not partake in ceremonies or festivities that are common in mainstream societies, such as birthdays or anniversaries. In fact, they laughed at the notion of holidays and celebrations based on human milestones when questioned about their opinions on the subject. They have one festival a year to praise Buddha. The entire community congregates at the local Buddhist shrine or at the cave where the Chief was born for their yearly puja. The exact date varies each year and is chosen by community members, but it is usually held during the dry season. The number seven has cultural significance among the Danigala Veddas. When their first chief and his wife located themselves in the Danigala region, they had seven sons from which the seven acknowledged family lines in the community originated. Furthermore, family chronicles are only passed on for seven generations. The current chief knows the history of the prior seven generations, but he has passed on to his sons only stories of the six most current generations. Including their father's tale, they know ancestral stories of seven generations. When questioned why they practiced this method of passing on family history, the Chief replied, "Anymore and it would get confusing. Seven is a good number." Today, there are about 300 people who identify themselves as Danigala Veddas. Like many indigenous populations across the world, the Vedda people are slowly becoming inculcated with Western thought and custom and are losing their own identity. Their language, for example, is no longer spoken as it has been replaced with Singhalese. Only the elder members of the community remember traditional Vedda words and definitions. Their subsistence practices have also been severely altered. Their hunting rights have been revoked as a way to protect the jungle animals. However, the Veddas believe that they are better protectors of the jungle animals than the Government. According to the Chief, the Vedda people know how self-regulate to keep the system balanced. They know the animals that are plentiful and those that are scarce and hunt accordingly. They do hunt just for sport or kill animals that are not in abundance; they only hunt animals that are unstinted when they require meat as food. Additionally, the Veddas emphasize the need for balance with the jungle flora. They desire the cessation of destructive deforestation to keep the forest plush as well as diverse. Many plants that the Veddas rely on for medicinal purpose have become scarce due to modern land use. The Vedda people feel that they are better qualified to protect the land than the Forest Department because they not only live in the jungle, they are part of it. The Veddas are making a plea to have their rights to their traditional land restored. They have had generations of experience living in balance with the jungle. Given the opportunity, they would make ideal protectors or the land and keep the forest animals, plants and humans in harmony. This article first appeared in The Sunday Times (Colombo) of Sunday, 10 October 2004 |

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |