|

||||||||||

A Plan to Protect Bio-diversity and Indigenous Culture in Sri Lanka

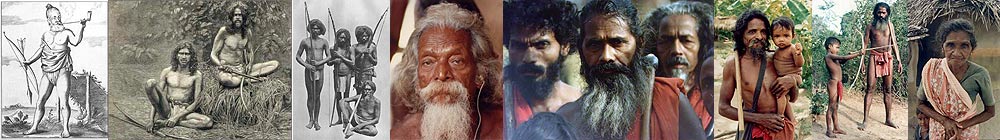

A proposal by Cultural Survival of Sri LankaBackgroundSri Lanka's indigenous 'first people', the Veddas or Wanniyalaeto ('forest-dwellers') as they call themselves, have inhabited Sri Lanka's semi-evergreen monsoon dry forest, the Wanni, for at least 16,000 years and probably much longer. To this day, their detailed knowledge of their habitat, including its fauna and flora, remains unsurpassed. Development activities in the twentieth century, however, have drastically reduced both the Wanniyalaeto people and their traditional forest habitat to the extent that unless measures are taken soon, not only many species of fauna and flora but also the indigenous human culture that successfully managed the forest environment for millennia face almost certain extinction.

Under the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Scheme, in 1983 hundreds of Wanniyalaeto families were compelled to abandon their traditional forest habitat and livelihoods and to accept translocation and settlement onto government colonies with the object of assimilating the semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers into mainstream Sinhala society by converting them into rice cultivators. Their last forest enclave, a 198.72 square mile catchment area in eastern Sri Lanka, was alienated from them in 1983 to create the Maduru Oya National Park, which nevertheless continues to be subject to rampant game poaching and illicit deforestation. Deeply disturbed by the devastation wreaked upon their ancestral hunting grounds and upon the social cohesion and cultural integrity of their ancestor-revering culture, many Wanniyalaeto have opted to return to their ancestral way of life. But when twenty-one Wanniyalaeto families sought to re-occupy their former habitat in May, 1992, they were refused entry by Wildlife Department officials backed up by armed police. More recently, however, the Sri Lanka government's policy towards its indigenous citizens and their role in the development process has undergone changes reflecting a more sympathetic perception of indigenous aspirations. In particular, with the growing recognition of a precipitous drop in the island's forest cover and related adverse effects upon wild- life and general fertility from reduced rainfall, the government is now more inclined to avail itself of Wanniyalaeto expertise in protecting the remaining forest cover and wildlife. A final window of opportunity to preserve bio-diversity and indigenous culture simultaneously now presents itself, but for a short time only before it is too late. A plan is now being formulated by the NGO Cultural Survival of Sri Lanka in consultation with the Wanniyalaeto that will eventually return the day-to-day management of the Maduru Oya National Park back to the Wanniyalaeto with the active cooperation and participation of the Ministry of Lands, Irrigation and Mahaweli Development, the Ministry of Environment, and other concerned ministries and international development aid agencies. Advantages and BenefitsThe plan's elegance lies in its simplicity, since by allowing for the phased return of Wanniyalaeto families to occupy and manage their ancestral habitat as they had been doing for uncounted millennia, it will:

Features

The Cultural Survival plan also provides for:

Text submitted to Sri Lanka's National Committee for the International Year of the World's Indigenous People in 1994 by Cultural Survival of Sri Lanka. Contact Cultural Survival advocate Patrick Harrigan: info@LivingHeritage.org. See also:

|

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |