|

|||||||||||||||||

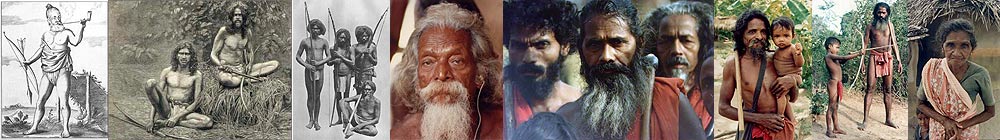

Colonial Histories and Vädda Primitivismby Prof. Gananath ObeyesekerePart Four: Väddas and the Resistance (1817-18)

Vädda loyalty to the Kandyan king is seen with extreme clarity and detail when the Sinhalas and Väddas of Vellassa and Viyaluya began their revolt against the British in 1817 and which soon spread all over the Kandyan provinces in the most serious challenge to British rule ever mounted in Sri Lanka.57 The rebellion itself began over local issues related to the district of Vellassa in and around the region near the modern town of Bibile.58 The Muslim traders who were loyal to the British lived in three villages in this area but they were as always under the control of Sinhala chiefs. When Governor Brownrigg in a tactical move to control local chiefs gave the Muslims their own chief or Muhandiram the Sinhala nobility in the area harassed them. This anti-Muslim movement later lead to resistance against British rule itself when there emerged a claimant to the throne, Dorai Svami, who was believed to be in the direct line of descent from the Nayakkar kings. He wore the robe of a Buddhist monk and proclaimed himself king in the Kataragama devāle, demanding the sword and regalia left by the deposed king and when these were granted he toured the area of Vellassa in royal style.59 At Pubbare he was received as royalty and he exchanged his robe "for a white and a colored cloth, a fine shawl, and a red turban embroidered with gold which Kivulegedera [a Vädda chief] produced."60 Soon the notorious D'Oyly, the government resident in Kandy and master spy for the British, found that Dorai Svami was in Kokagala, the sacred peak for the Väddas in the Bintanna area, under the protection of Kivulegedera Mohottala. "There the Prince proclaimed that Kataragama Deviyo had given him the Kingdom which foreigners had seized, and that he was the third in line in descent from Raja Sinha, imprecating on himself the God's vengeance if what he stated was untrue."61 The Rate Rala of Maha Badulugama prostrated himself before the Prince and swore allegiance while Kivulegedera Mohottala was proclaimed Disava of Valapana, the area west of his own division of Viyaluva. Who was Kivulegedera? He belonged to a distinguished line of Bandara Väddas and he was also a Mohottala, that is, an important Kandyan official. Kivulegedera itself is a village in Viyaluya, a district adjacent to both Vellassa and Valapane. It is one of the most beautiful villages I have seen in the dry zone, ringed by mountains on one side and fed by a perennial stream (kivula). What is striking from the point of view of this paper is that throughout the rebellion the Prince sought refuge in this wild country under the protection of the Väddas and was escorted by them. During the height of the rebellion when D'Oyly sent his stooge, Udugama Unnanse, a Buddhist monk and spy for the British, to seek the Prince, the latter not only gave this monk permission to visit him but he even "furnished him with an escort of Väddo." The claimant's palace itself was a makeshift affair but it was still considered a temporary capital or a "gamanmāligāva" or "circuit palace" with much of the symbolic meanings attached to the "city" of the king. The next phase in the British search for Dorai Svami was when D'Oyly ordered John Sylvester Wilson, the Resident of Badulla and a thoroughly decent colonial officer, to seek information about him. Wilson dispatched a party of Muslims who proceeded to Dankumbura in Bintanna only to learn that the "stranger," as the claimant to the throne was called, was eight miles north in Keheulla with an armed guard of two hundred Väddas. But the British force was confronted at Bakinigaha by a large force of Sinhalas who captured the Muslim chief. He was taken to the Prince and sentenced to death. When Wilson was informed of this disaster he himself went into this area and once again had to deal with armed Sinhala villagers under local chiefs. Wilson tried to negotiate with them but they would have none of it. He sent his force back and retired into the stream nearby in order to defecate. There he was killed by Sinhala arrows: a not very-glorious way of dying, a not-very-glorious way of killing. Yet, who shot Douglas Sylvester Wilson is as much of a point of honor for Sinhala people in this area just as who killed Captain Cook was for Hawaiians.62 To this day various Sinhala families in Vellassa vie with each other for that somewhat dubious honor.63 A week after Wilson's death the Prince "assumed the name Viravikrama Śrī Kirti and appointed the Household officials whom court etiquette rendered necessary."64 Simon Sawers, D'Oyly's trusted second in command, was sent to Badulla on 27 October, 1817 to oversee matters. The well-known Kandyan chief Kappitipola Nilame was also sent by D'Oyly to Badulla and another chief Dulvava was sent to Valapane, the region which was given to Kivulegedera by the Prince. Kivulegedera's people chased Dulvava away and tore his banner to shreds and destroyed the mail station that connected this region with Kandy. The British strategy was to isolate the region and this was done by the infamous Major Macdonald who with four detachments moved from Badulla, Kandy and Bintanna and met on the 31st at Haunsanvella, near the place of Wilson's death. He engaged in a massive destruction of villages and their crops. There was only one casualty on the British side, a man who was shot when Kivulegedara's house in Viyaluva was being burnt down.65 As Pieris rightly pointed out scorched earth tactics, though well-known in Europe and practiced in colonial warfare, were unthinkable for Kandyans for whom destroying crops were almost acts of sacrilege. On November 1st Molligoda and Millava joined the British troops under Macdonald and marched from Bintanna with no opposition, "crowds appearing before the Adikar to claim protection from him." Yet the Prince eluded capture. In a proclamation dated 1 November 1817, Brownrigg urged the punishment of those "acting, aiding, or in any manner assisting in the rebellion which now exists in the Provinces of Oowa, Walapona, Wellassa and Bintanna ... according to Martial Law either by death or otherwise, as to them shall seem right and expedient."66 Kappitipola's fate was different from Dulvava's. He left Badulla as an emissary of the British to deal with the situation in Vellassa but he was captured by Väddas at Alupota, a Muslim village, on November 1, 1817. According to one local history I gathered in the field it was again Kivulegedera who headed the Väddas. Apparently Kappitipola was effectively surrounded by a force of Sinhalas and Väddas and they refused to let him leave. The details of the negotiations between Kappitipola and those who captured him are not clear; what is clear is that Kappitipola, from being the agent of the British government, now became the leader of the rebellion. With Kappitipola's involvement the rebellion ceased to be a local one and became a national movement in 1818. For our purposes I want to deal with the arrival of Dorai Svami with Kappitipola near Alutvela (where a temporary palace was erected). Dorai Svami appeared in full panoply just as was the case with any Sinhala monarch. Paul E. Pieris has a vivid description of this event but let me refer to his discussion of the ceremonial role of the Väddas in this formal portrayal of the official structure of the Kandyan state. "The royal parasol, headdresses, and other insignia were brought out and arranged after which a hundred and fifty armed Väddo came swiftly and silently out of the woods and took up their station. The horanava sounded again and a procession emerged with the arms of the Gods... The Chiefs now ranged themselves according to precedence, and out of the forest the King [Dorai Svami] appeared covered in white draperies from head to foot and guarded by a hundred Väddo, crossing the threshold of the building at eight paya [Sinhala "hours"] before dark, which was probably the auspicious nakata, while the Väddo stationed themselves around it. Five paya later the Chiefs assembled again before the Sarasvati Mandapa and on the Prince showing himself at a window prostrated themselves in homage before him."67 The details of the suppression of the rebellion are not germane for the present argument except to mention the extraordinary show of force and brutality by which it was crushed. As late as 1896 the British judge Archibald Lawrie could give some details on the ruined temples and devales in the Central Province during this fateful period and write about the event itself: "The story of the English rule in the Kandyan country during 1817 and 1818 cannot be related without shame. In 1819 hardly a member of the leading families, the heads of the people, remained alive; those whom the sword and the gun had spared, cholera and smallpox and privations had slain by hundreds."68 The pax britannica that followed the rebellion was erected on this terrifying base. Kivulegedera himself, along with the other leaders, was captured and executed while large numbers of lesser leaders were deported, sometimes without trial, to Mauritius, the penal colony of the time. After his death he was deified as Kivulegedera Punci Alut Deviyo ("the younger new god of Kivulegedera"). According to Paul E. Pieris, Kivulegedera Mohottala was the last and seventh of a distinguished line of deified Bandara Väddas.69 Both this deity and his father, also a deity, are to this day propitiated in communal rituals among the Sinhalas and Väddas in the Bintanna, Vellassa and Viyaluya region. However, few today seem to think that Kivulegedera was a Vädda at all; he has been transformed into a fully Sinhalized hero of the resistance. End Notes

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Living Heritage Trust ©2024 All Rights Reserved |