By Zinara Rathnayake

The Veddas were traditionally forest dwellers, who foraged, hunted and lived in close-knit groups in caves in the dense jungles of Sri Lanka. But most people haven’t heard of them.

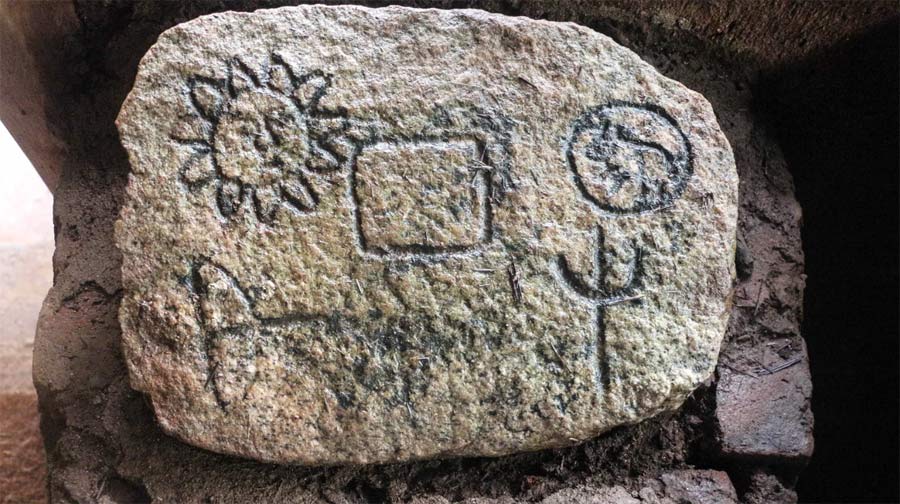

“This is our cave,” said the man. He was tall with curly, shoulder-length hair and his lower lip was caked red with the areca nut he was chewing. An orange sarong was tied around his waist and a small axe was slung over his left shoulder. He pointed at a dimly lit rock shelter guarded by swaying trees.

“This is where the children lived,” he said, gesturing to a dark corner, “and here, the men and women. You see the top there,” he continued, showing a sun-lit platform sheathed by scattered boulders. “That’s where our leader slept, and we burnt wild boars, deer and rabbits to eat.”

Gunabandilaaththo belongs to the Vedda community, the earliest known aboriginal people of Sri Lanka. For centuries, his people were forest dwellers who foraged, hunted and lived in close-knit groups in caves in the dense jungles of Sri Lanka, relocating from one cave to another when someone from the group died. After one’s death, they laid the body on the cave floor and covered it with leaves while gathering by a large tree to pray for the deceased; and offered wild meat, honey and wild tubers to their ancestors and the deities of the trees, rivers and jungles. “We prayed for their afterlife so that their souls will belong to the deities; they will look after us,” he said.

Today, the Vedda live scattered in tiny settlements in the Hunnasgiriya hills in central Sri Lanka up to the coastal lowlands in the island’s east. However, long before Indo-Aryans – who are now the dominant Sinhalese-Buddhist people – came to Sri Lanka from India around 543 BCE, the Vedda lived all around the island.

Despite being Sri Lanka’s earliest inhabitants, many people know little to nothing about them. For many centuries, Veddas were stigmatised and oppressed by the Sinhalese rule, and limited only to tourist interest. Today Veddas are thought to account for less than 1% of the national population.

As with many indigenous groups, there’s little evidence to suggest their origins. Archaeologists connect their gene pool to a prehistoric human called Balangoda Man, who lived 48,000-3,800 years ago and was named after the historical sites in the town of Balangoda – where his skeleton was first discovered – 160km from Colombo.

Gunabandilaaththo belongs to the Danigala Maha Bandaralage lineage of Vedda, a Sinhalese title given to them by the kings of the Kandyan kingdom (1476-1818). Originally, they lived in eastern Sri Lanka, in the Danigala mountain and the surrounding forests. But the construction of Senanayaka Samudra – the biggest man-made lake in Sri Lanka – in 1949, displaced this Vedda community.”We lost some of our original forest homes because of the reservoir,” said Kiribandilaaththo, who also belongs to the Danigala Maha Bandaralage lineage. During that time, seven families from Danigala came to live in a cave in Rathugala village in eastern Sri Lanka, which Gunabandilaaththo had shown me earlier. “My ammilaaththo and appilaaththo (mother and father)… they were part of that group,” he said.

“[The government] had asked our ancestors whether they liked to eat rice,” Gunabandilaaththo added, explaining that the government encouraged them to relocate to Sinhalese villages for rice farming. Most Veddas agreed; those who did not – including the seven Rathugala families – received no compensation from the government.

Those that relocated had little choice but to assimilate into Sinhalese culture and intermarry with the Sinhalese. Because many Sinhalese people considered them backward and uncultured, most of them, Gunbandilaaththo said, changed their names to hide their Vedda heritage. Even their language evolved, adapting Sinhalese words to communicate with others.

While the seven families who lived in the Rathugala cave held onto their traditions for a little longer, living in the jungle and hunting and foraging for food, they gradually mingled with Sinhalese farmers and Muslim traders from nearby towns. When food was scarce in the jungle, Gunabandilaatho’s parents cultivated grains like corn, finger millet, mung beans and black-eyed peas. “We slowly started losing our way of life,” he said.

But now, things are slowly changing, with the Vedda community reclaiming their heritage along with renewed interest in these first people of Sri Lanka. “The Sinhalese used to look down upon us,” Gunabandilaaththo said, “but things have changed now. People are more educated, and they are interested in knowing about us.”

The Department of Archaeology and the Ministry of Heritage built the Veddas Heritage Centre in Rathugala just before the pandemic, where Gunabandilaatho will be leading tours for visitors, starting in April.

Proud to share his culture and traditions, Gunabandilaattho took me into the centre’s small mud cottages, which are next to the cave where their ancestors resided. One was decorated with black-and-white pictures captured by the physician Richard Lionel Spittel, who often visited the Vedda habitats in the early 1900s. Another was decked with pictures of caves, a map of their original homes and statues of Veddas. Visitors can also request to see traditional ritual dances or to listen to their prayers and music.

“We want to pass our cultural elements to our younger generations,” Kiribandilaaththo said, explaining that he’s happy to have the centre. Although briefly halted by the pandemic, Kiribandilaaththo conducts indigenous classes for 22 Vedda children every weekend at the centre, teaching them about their way of life and their language and traditions.

“When we were small, our parents took us to the jungle. They showed us the caves, where to drink water, and how to find our food so we would never go hungry. They showed us the streams that never dried up. So, when we go to the jungle now, we can tell if an elephant or a wild bear is near us; we smell them,” Gunabandilaaththo said. “We want to give the same knowledge to our small children. We teach children to never pluck a flower or a leaf from a tree if you don’t have any use for it.”

Today, most Vedda people are Buddhists, but their animist beliefs are still deeply etched in them. “We teach children to never pluck a flower or a leaf from a tree if you don’t have any use for it,” Gunabandilaaththo said, “and never cut trees near a river stream because it will dry up.”

Umayangana Pujani Gunasekara, an indigenous food researcher and author of Vedi Janayage Sampradayika Ahara Thakshnaya (Traditional Food Technology of the Sri Lankan Vedda), explained that for a long time, Veddas have been viewed as a tourist interest in Sri Lanka. The community in Dambana, a village 65 km from Rathugala and home to the Vedda of Uru Warige lineage, for example, is heavily commercialised. “Most people complain that Veddas ask for money to even explain about their history and traditions,” Gunasekara said. “But you can’t blame them. When government regulations like Forest Ordinance came into place, they couldn’t go hunting in the jungles. They lost their environmentally conscious traditional lifestyle and their access to foodways. So, they needed a way to survive.”

Currently, Veddas in Dambana have to haggle to sell their crafts to tourists, who often visit the village to take photos with the chieftain.

“But, of course, authorities can have a tourism framework where it uplifts the community, both economically and socially, allowing them to preserve their heritage,” Gunasekara said. Both Gunabandilaaththo and Kiribandilaaththo are also hopeful that tourism can bring a positive change to the community.

The newly opened Wild Glamping Gal Oya, where visitors can stay in luxury tents in the forests around Rathgula, is already doing that: 13 staffers, including the hotel’s chef, are Vedda people from Rathugala, while the hotel’s onsite organic farm employs several others. “Some of these young people used to move away for jobs, but they are working here now,” said Gunabandilaaththo, who also guides hotel guests on hiking tours and sometimes takes visitors to Danigala, their original home. “People come from Colombo – and they are excited to know about our culture and hike our mountains with us.”

The Vedda staff members, who are mostly in their 20s, conduct cooking sessions for guests, preparing dishes stemming from their culinary traditions like smoked meat, wood-fired cassava roots and finger millet roti. That’s because while many young Veddas know little of their heritage and traditions, a love for their cuisine remains strong. Many still go foraging in the jungle for days at a time, sleep in the caves, and fish and hunt wild animals to cook over fire. They bring back wild meat, honey and wild tubers.

“I still cook our food for my children and grandchildren,” said Dayawathi, whose mother is Vedda and father is Sinhalese. She cooks curry for breakfast made of corn, wing beans, spine gourd and black-eyed peas, very different to the creamy vegetable curries made with coconut milk found in most island homes. While most Sri Lankan dishes are spice-laden, Dayawathi said she doesn’t add spices. “Instead, we mash green chillies and make a paste and eat it with helapa, which is a soft, steamed traditional finger millet dough wrapped in leaves.”

“For lunch, we sometimes add a piece of smoked meat to the same curry,” Gunabandilaaththo added, explaining that they also preserve smoked wild meat in honey poured into a gourd. “I mostly eat steamed jackfruit and wild meat, and I’ve never been to the doctor,” he said.

However, as the second chieftain of the Rathugala Veddas, Gunabandilaaththo understands that they need recognition and support. Not only does Sri Lanka not have specific laws to protect its indigenous people, but government acts continue to prevent them from accessing their traditional hunting grounds – and a 2017 UN Human Rights review highlighted that Veddas are economically and politically marginalised.

“The government has always abandoned us. If they recognise us and our very existence, it would help us preserve our culture better,” Gunabandilaaththo said, explaining that his community conducts a monthly meeting to talk about the need to preserve their traditions. Some young people feel strongly about their heritage, he said.

“We were here before King Wijaya [the first Aryan king] came. We are the oldest living inhabitants in the country – and I want everyone to know that we exist here. I want everyone to know that we have our language, and we want to take it forward.”

Courtesy: BBC World Service

Leave a Reply