by David Blundell

455-26th Street, Santa Monica, CA 90402 USA

Abstract

This paper addresses the potential of intangible folk life as a continuum amounting to world heritage in a country of magnificent UNESCO listed sites. If the indigenous Vedda (Vanniyaletto) of Sri Lanka are the heirs of an existence dating back to the Mesolithic of Southern Asia, then this community represents a sphere of cultural expression that requires world attention in conserving a folk diversity that is rapidly disappearing in this century. Yet to date these Vanniyaletto, living in a land of significant ancient world heritage, are struggling to have a museum or community center dedicated to their existence. They are a people wrapped in the matrix of the Sinhala and Tamil communities from earliest times, yet relegated as fringe curiosities at best, seen without an acknowledged contribution to national program.

Sri Lanka and Its World Heritage

Sri Lanka is an island with a written history that includes 2500 years, and by the first millennium AD its civilization and cultural heritage were being transferred throughout many parts of Southeast Asia (Figure 1). Heritage consciousness in Sri Lanka has been gaining momentum since the revival of interest in its ancient Buddhist civilization with the establishment of the Archaeological Survey under British colonial rule in the 19th century. In Sri Lanka during the first half of the 20th century, the British led the quest for excavating ruins and cultural remains in the Sri Lanka jungle, giving impetus to the eventual establishment of national aims. These aims were validated with the establishment of world-recognized sites of culture following the legacy of Anuradhapura civilization, which comprised other historic ancient cites, temples, and monuments, forming the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Cultural Triangle of Heritage. Unfortunately, compared to the historic monuments and other tangible artifacts, the more intangible living treasures in Sri Lanka, such as the folk traditions of the living culture, until recently have been neglected, or at best seen as a curiosity.

Since the mid-1980s, Sri Lanka has embarked on a course of having its sacred and historic national monuments designated as world heritage sites under the auspices of UNESCO. Archaeological sites are scattered in a cultural triangle in the central northern regions of the country. The Dutch colonial walled town of Galle is the exception at the southern end of the island away from the ancient civilizations. Galle with its harbour and fort is one historic site that includes a living population. The other is the town of Kandy in the central highlands. Kandy is especially unique as a royal pilgrimage site and the seat of the last ancient kingdom (14th to 19th century). It is a living treasure of ritual and worship with an annual pageant of the Tooth Relic Shrine (Dalada Maligava) dating back, in its ritual expressions, to the 5th century in Anuradhapura. Another two previous historic capitals include classical Anuradhapura from approximately 500 BC to the tenth century AD, and Polonnaruva from AD 993 to 1235.

The ‘Cultural Triangle’ was initiated when the UNESCO-Sri Lanka team, preparing the action plan for the campaign, noticed that there was an array of monuments or sites that needed international attention and assistance. The six Cultural Triangle sites were selected on the merits of their uniqueness in history. For the initiator of civilization in Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura civilization flourished with its Abhayagiri Monastery having 5000 Buddhist monks by the 5th century, thus being one of the largest religious institutions in history. Also at Anuradhapura, Jetavana Monastery claimed the largest stupa in the world at 404 feet in height.

After the collapse of the hydraulic civilization of Anuradhapura, a city further to the southeast of the northern plain, Polonnaruva – where the institution of Alahana Parivena flourished as a great university in the 12th century – took up the mantel. Other unique sites were chosen featuring an early paradigm of sacred palatial water gardens at Sigiriya, the 5th century paramount rock formation styled abode of the ‘god-king’ Kassapa I. Also, the Golden Rock Temple Shrine of Dambulla with 20,000 square feet of painted murals in five cave shrines dating from the 7th to 18th centuries was selected as a treasure.

The single natural site is the Singharaja Forest Reserve. It is a unique, lofty, cloud-shrouded eco-niche richly endowed with a newly discovered and a classified endemic species of wildlife. The Cultural Triangle was facilitated by the Board of Governors of the Central Cultural Fund, which is composed of the Prime Minister as chairman together with six Cabinet Ministers and several other high level officials coordinating and managing the campaign activities. The commissioned work from UNESCO with a budget of US$54 million employs about 4,500 personnel staff working with another 500 graduates in archaeology, architecture, and other related disciplines including administrators (Roland Silva pers. comm.).

The designated heritage sites are precious to the people of Sri Lanka and are often visited by local people as a means of reinforcing their cultural identity. Pilgrims following their ritual Buddhist practice en route to the shrines of the ancient cities make a stop at the historic museums looking at the artifacts of past ages. Yet, the intangible indigenous aspects to the culture are not observed as much as are the monumental sites.

Folk Life: Vedda Heritage

With the established cultural monuments making international rosters by the national government and UNESCO, the intangible living heritage that exists in Sri Lanka has been treated as a curiosity, with some embarrassment among better-educated urbanites. Yet, innumerable intangible elements of culture exist away from the mainstream. What is the worth and value of local performance such as tovil (exorcism), drumming, low-country dance, puppetry, palm leaf weaving, ocean-going catamaran making, and innumerable other living folk crafts? Every location in the country has separate traditions, yet related because they come from Sri Lanka. Understanding the contemporary sources and uses of these life ways is vital to appreciating a previous life that lends itself to what is called local heritage. My work is based on research among the Vanniyaletto communities (Vedda), to whom I was first introduced to during 1973, 1975-1976 and 1981 at Dambana, Mahiyangana. I conducted later research at Dambana in 2002-2003 (Figure 2).

(photo by author)

The indigenous people of Sri Lanka, the Vedda, have been recorded in the ancient palm leaf chronicle Mahavamsa. The term ‘Vedda’ (or ‘hunter’) is a name given by Sinhala-speakers, while “Veden” is the term used in Tamil. The people refer to themselves as Vanniyaletto or Vanniyalatto (forest or nature dwellers). The first Western account was published by cast-away Robert Knox in 1681 (An Historical Relation of the Island of Ceylon). In Germany as early as 1881, a report was published on the Vedda by physical anthropologist Rudolph Virchow, translated into English as The Veddhas of Ceylon and their Relation to the Neighboring Tribes (Virchow 1886). The Veddas by C. G. and Brenda Z. Seligmann appeared in 1911. Throughout the 20th century a number of academic studies of language and culture of the Vedda have been conducted (see Parker 1909; Goonetilleke 1960; Wijesekera 1964; de Silva 1972; de Silva 1990; Dharmadasa and Samarasinghe 1990; Meegaskumbura 1993; Ramanayake 1995; Silva 2002). These studies have occurred especially in the Mahiyangana/Maha Oya areas (e.g., Seligmann and Seligmann 1911; Spittle 1941), Anuradhapura (e.g., Brow 1978), and the east coast (e.g., Dart 1990).

Dart (1990:80) tells us ‘The Veddas have a long history of existence as a distinct group, and have maintained cultural traditions which are distinct from those of present-day Tamils and Sinhalese.’ The Vanniyaletto believe in transmigration of human spirit that allows for ancestors known as nae yakku to assist with matters of the living. Each person in the community is enabled to call on nae yakku for specific assistance (Dabana Gunawardhana 2003 pers. comm.; see also Puspahumara 2000; Obeyesekere 2002; n.d.).

Another common feature of the Vedda communities is that they occupy a border situation “as a buffer” among the Sinhala and Tamil communities, for example in the Mahiyangana region for the Sinhala and the East Coast for the Tamil. According to Brow (1978:36), there is a parallel sense of relatedness between the Sinhala-speaking Vedda and the Tamil-speaking Vedda, as one between people connected in terms of societies and regions. Today their populations range in a swath across from southeast of Anuradhapura to the east and south, including parts of the central mountains to the east coast and again south to Bibile. Yet in earlier times their extent covered the entire country where nature offered a bounty of resources.

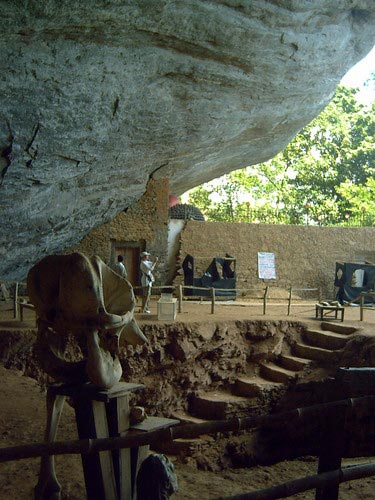

Overall, Sri Lanka has been inhabited by Mesolithic societies for about 30,000 years with evidence discovered in Fa Hien Cave at Pahiyangala (Figure 3 at right). It is probably the largest cave site of its kind in the land near Balangoda, and was first examined by Deraniyagala and Douglas Osborne in the late 1960s. A 3.75 meter habitation deposit rich in charcoal provided evidence of a Mesolithic industry and habitation site with the remains of worked stones, dried food, shells, animal bones and people. The term Mesolithic was used from the late 19th century to define the transition period from hunting and gathering to food producing societies (Kennedy 1984). Also, such remains were found in prominent caves such as Kitulgala and Batadomba. I especially mention Fa Hien Cave for there is a historic connection. It was here at Pahiyangala that the famous Chinese Buddhist mendicant, known as Fa Hsien, sojourned at the cave in the 5th century AD during the reign of King Mahanama. Currently, a Buddhist shrine remains in the centre of the cave with a reclining Buddha statue and a side chamber dating from the Kandyan era of the 17th-18th centuries.

Kennedy affirms that there is a biological-historic continuum with the Vedda connecting with early occupation at Batadombalena (ca. 31,000-13,000 BP) and other sites where Mesolithic remains have been excavated, such as Belilena Kitulgala (ca. 30,000-9,000 BP), Bellanbandi Palassa (ca. 6,500 BP), and the Pahiyangala caves. These are now the earliest known anatomically modern humans from South Asia (Kennedy cited in Deraniyagala 2002).

Indications show that the region was exploited for fauna during this entire time-span in a similar way. These remains are similar with other early hunter-gatherer sites in Monsoon Asia generally (Kennedy and Deraniyagala 1989). A skull found at Fa Hien Cave, Pahiyangala, has been dated to 37,000 BP making it the oldest Mesolithic find in South Asia. I mention this as the continuum is important for understanding such a rich and ancient past in the context of the historic era. Historically and epistemologically the term vedda refers to a hunting group from the Sanskrit vyadha and has been applied to various tribes in Southern Asia, including Borneo and Sumatra. These forest-resource gatherers live in groups of about one to five families with four to ten members in a family (Deraniyagala 1992:387). Among the Sinhala-speakers, this term Vedda is a reference to a small scale hunting and gathering community that interacted with the kings of Lanka for 2,500 years.

The Vedda have been compared to the Kadar and Chench of continental South Asia and in Southeast Asia with the Andaman Islanders and the Semang of the Malaysian Peninsula (Deraniyagala 1992:395-429). In ancient Sri Lanka, forest dwellers to in the 7th century were referred as Yakka by the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Hsuien Tsang, who stated they were in the southeast of the country (i.e., Bintenne). Another group known as the Naga were present at the arrival of the Sinhala with Prince Vijaya in the 5th century BC, yet became displaced in history. In the Sinhala chronicle Mahavamsa it was the indigenous Yakka princess Kuweni who married Vijaya, who became the first recorded Sinhala king. Thus, the Sinhala-speakers claim partial hereditary descent from the Vedda, as their own heritage officially testifies in the Mahavamsa.

Throughout the ages of the ancient kingdoms from Anuradhapura to the Kanydan rulers, the Vedda were treated as highly appreciated and respected members of the royal court. They were scattered across Uva Province, Central Province, and Eastern Province. Their responsibility to the state included the heraldry of the ritual perahera, honouring Buddhist shrines in procession, such as the Temple of the Tooth (Dalida Maligava) in Kandy, and supplying the essence of the natural land to the nobility. According to Obeyesekere, the Vedda were treated as high nobility, considered brothers to the Nayaka kings of Kandy.

In 1817-1818 the Vedda rallied with an upstart Sinhala insurrection against the newly established British rule over the entire island, displacing the authority of the up-country Kandyan rulers. The rebellion was crushed by the British, eliminating the local aristocracy and the Vedda population, and Vedda influence as an ethnic group declined throughout the 19th century. By the turn of the 20th century, they were considered to be on the verge of extinction (Seligmann and Seligmann 1911), or soon to be absorbed into the Sinhala and Tamil populations (Deraniyagala 1963; Dharmadasa and Samarasinghe 1990). In the mid-20th century Mahaweli River irrigation projects have provided farmlands for the Sinhala population to expand into the Vedda’s life support regions. Now, where irrigation systems have been renovated and made available since the 1950s, thousands of Vedda have opted to resettle and engage in paddy cultivation along with the Sinhala farmers acquiring land in the Mahaweli River plain.

In the last few years, Uruwargiye Vanniyala, the successor and son of elder Tissahamy at Dambana, near Mahiyangana, estimates that there are 800 people holding to ‘traditional’ Vedda community values. James Brow’s 1978 published study refers to the Anuradhapura Vedda as self identified, at about seven thousand Vedda descendants cultivating paddy, yet admittedly a Sinhala cultivator assimilated population.

A few curious tourists, both local and from abroad, make their way to the periphery of a national wildlife reserve to visit the village of the Vedda at Dambana, near Mahiyangana. Yet, with Sri Lanka demonstrating its own historic and reconstructed past in conjunction with the cultural and political integrity, the Vedda continue to offer living values. Are the Vedda a microcosm of ethnic heritage concern in South Asia? Their recognition is crucial at this time in view of the current developments towards peace after years of unresolved civil war since 1983 in Sri Lanka.

The Vanniyaletto community is one of the most well-established ethnic groups historically documented, yet neglected as a knowledge-based community in Sri Lanka’s historically plural society. In its complex and lengthy ethnohistory (Deraniyagala 1992:395-429), what values are retained in their way of life in eastern and central Sri Lanka that could be useful to know? Since 2000 in the Uva Province in Mahiyangana, Moneragala, and Badalkumbura districts, a project named “Documentation and Using Indigenous Knowledge” has been underway to search out and record systems of local knowledge in order to promote this as something of worth and sustainable value in the current generation.

As the Green Revolution of South Asia began in the 1960s, indigenous knowledge declined in Sri Lanka. Therefore, only in remote places is the old way of life found. The project combines two aspects: (1) agrobiodiversity for sustainable farming and (2) traditional health practices. K.A. Jayaratne Kahandawa, based in Badulla (Uva) has been assisting non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working on development projects such as the Norwegian funded “Future in Our Hands,” ‘and the SANFEC–South Asian Network on Food Ecology and Culture. These programs investigate the valuable utility of herbal medicines and knowledge of flora understood by the Vedda and local rural communities. Quietly, these ‘people of nature’ are being appreciated as valuable resources of local knowledge.

Of course, the national mainstream population is curious and proud of such people living in Sri Lanka. However, their heritage stemming from their ‘indigenousness’is not proactive with the local communities. The museums and cultural centres in Sri Lanka were built as static institutions of cultural inventory honouring literate civilization.

If the Vedda are the heirs of an existence dating back to the Mesolithic cultures of Southern Asia, this community represents a sphere of expressions that requires world attention in conserving a folk diversity that is rapidly disappearing in this century.

Conclusion

The Vedda live in a syncretism of heritage beliefs and ways of doing things stemming from local origins that weave together a contemporary society (Obeyesekere 1982). Specific knowledge is found among the Vedda in terms of the forest and belief systems based on nature. This knowledge-sharing is a valuable asset as intangible cultural heritage that could assist the neighbouring Sinhala and Tamil communities by introducing the use of local herbal substances. The Vanniyaletto communities are intentionally few in the numbers of a group as they are reliant on limited natural resources. These groups have remained essentially peaceful throughout their history, without initiating violence against other groups (Gunawardhana 1993). Yet to date, although the Vanniyaletto live in a land of significant ancient world heritage, they struggle to obtain a simple museum or community centre dedicated to their existence. They offer intangibles that are commonly ignored in a world of tangible monuments.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my colleagues in Taiwan, Sri Lanka, and USA for their support in preparing the initial IPPA Taipei Congress paper drafts. Originally I had planned to include the cultural resource management developments in Southeast Asia reflecting on the programs of the Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts Centre of the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) hosted by the Government of Thailand (SPAFA). Here I introduce intangible folk life as equal in heritage importance to the ancient monumental remains. Thus influenced by Gananath Obeyesekere in his article for The Hybrid Island (2002) and the recent Colonial Histories and Veidda Primitivism: An Unorthodox Reading of Kandy Period Texts (published online at www.vedda.org/obeyesekerel.htm and www.artsrilanka.org/essays/vaddaprimitivism/index.html I decided to incorporate the traditions of the Vanniyaletto into the equation of valued heritage resources.

My further thanks goes to Siran Deraniyagala, Douglas Osborne, and Kenneth Kennedy for their personal efforts to enhance my understanding of prehistory. K. A. J. Kahandawa of Badulla, Uva Province, Sri Lanka, introduced me to the work he is conducting on a valued living heritage on the verge of extinction, and how the acquisition of local knowledge could be useful to our modern society. Conrad Ranawake supported the project that included a field visit to the Dambana Vedda community. Dambana Gunawardhana, as the only university graduate in the Vedda community of Dambana, shared valuable knowledge. Roland Silva, President of International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) 1990-1999, and L.K. Karunaratne offered guidance for understanding the extent of cultural resource management in Sri Lanka for the ancient historic cultures.

References

Brow, James. 1978. Veddha Villages of Anuradhapura: The Historical Anthropology of Community in Sri Lanka. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Dart, Jon. 1990. “The coast Veddas: dimensions of marginality”. In Dharmadasa and Samarasinghe (eds.). The Vanishing Aborigines, pp. 67-83. Colombo: ICES

Deraniyagala, P. E. P. 1963. “The hybridization of the Veddas with the Sinhalese”. Spolia Zelanica 30(1):11-147.

Deraniyagala, S. U. 1992. The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective. Memoir Volume 8, Part I-II. Colombo: Department of Archaeological Survey, Sri Lanka.

Deraniyagala, S.U. 2002. The prehistory and protohistory of Sri Lanka – A synthesis. The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective. Chapter 7.

de Silva, C. R. 1990. “The Vedda and his mentors: some theoretical and methodological considerations”. In Dharmadasa and Samarasinghe (eds.). The Vanishing Aborigines, pp.34-47. Colombo: ICES.

de Silva, M. W. Sugathapala. 1972. Vedda Language of Ceylon. Munchen: R. Kitzinger.

Dharmadasa, K. N. 0., and S. W. R. de A. Samarasinghe, (eds.)

The Vanishing Aborigines: Sri Lanka’s Veddas in Transition. Colombo: International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES).

Goonetilleke, H. A. I. 1960. A bibliography of the Veddah. Ceylon. Journal of Sri Lanka Studies 3:96-106.

Gunawardhana, Dambane. 1993. The social organization of the traditional Vedda community. Soba 4(3):21-24.

Kennedy, K.A.R. 1984. “Biological adaptations and affinities of Mesolithic South Asians”. In J. R. Lukacs (ed.). The People of South Asia: The Biological Anthropology of India, Pakistan and Nepal. pp. 29-57. New York: Plenum Press.

Kennedy, K. A. R. and S. U. Deraniyagala. 1989. Fossil remains of 28,000-year-old hominids from Sri Lanka. Current Anthropology 30(3):394-398.

Knox, Robert. 1911. [1681] An Historical Relation of the Island of Ceylon. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons.

Mahavamsa. 1950. [1912] version by Geiger-Bode. Colombo: Ceylon Government Information Department.

Meegaskumbura, P.B. 1993. “The rituals and Santhi Karma (in‑ vocations) of Vedda community”. Soba 4(3):36-40.

Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1982. The principles of religious syncretism and the Buddhist pantheon in Sri Lanka. In Fred W. Clothey (ed.). Images of Man: Religion and Historical Process in South Asia, pp. 15-33. Madras: New Era Publishers.

Obeyesekere, Gananath. 2002. Where have all the Vaddas gone? Buddhism and aboriginality in Sri Lanka. In Neluka Silva (ed.), The Hybrid Island: Culture Crossing and the Invention of Identity in Sri Lanka, pp. 1-19. Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association.

Obeyesekere, Gananath. n.d. Colonial Histories and Vedda Primitivism: An Unorthodox Reading of Kandy Period Texts.

Parker, H. 1909. Ancient Ceylon. London: Luzac and Co.

Puspakumara, W. M. N. 2000. Rituals and Beliefs of Veddas. Unpublished MA thesis for Sinhala Special Degree. (In Sinhala)

Ramanayake, R. A. D. K. 1995. Bibliography on Veddahs. Delgoda: R. A. D. K. Ramanayake Publisher.

Seligmann, C. G., and Brenda Z. Seligmann. 1911. The Veddas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Silva, Neluka (ed.). 2002. The Hybrid Island: Culture Crossing and the Invention of Identity in Sri Lanka. Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association.

Spittel, R. L. 1941. Vanishing Veddas. Loris, 2(4): 195-201.

Virchow, Rudolph. 1886. The Veddhas of Ceylon and their relation to the neighboring tribes. The Journal of the Ceylon branch of the Royal Asiatic Society < 9(3):349-495.

Wijesekera, N. D. 1964. Veddas in Transition. Colombo: Gunasena and Co.