1994 report to Sri Lanka’s National Committee for the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People

by Patrick Harrigan of Cultural Survival of Sri Lanka

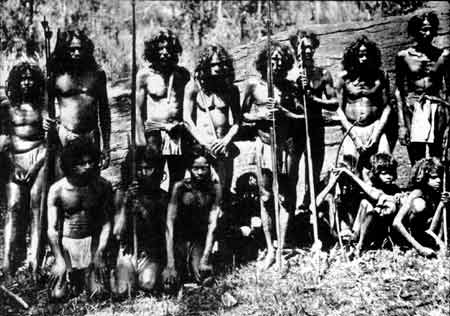

Sri Lanka’s indigenous inhabitants, the Veddas or Wanniya-laeto (‘forest-dwellers’) as they call themselves, preserve a direct line of descent from the island’s original Neolithic community dating from at least 14,000 BC and probably far earlier according to current scientific opinion.1 Even today, the surviving Wanniya-laeto community retains much of its own distinctive cyclic worldview, prehistoric cultural memory, and time-tested knowledge of their semi-evergreen dry monsoon forest habitat that has enabled their ancestor-revering culture to meet the diverse challenges to their collective identity and survival. With the impending extinction of Wanniya-laeto culture, however, Sri Lanka and the world stand to lose a rich body of indigenous lore and living ecological wisdom that is urgently needed for the sustainable future of the rest of mankind.

Historically, for the past twenty-five centuries or more Sri Lanka’s indigenous community has been buffeted by successive waves of immigration and colonization that began with the arrival of the Sinhalese from North India in the 5th century BC. Consequently, the Wanniyalaeto have repeatedly been forced to choose between two alternative survival strategies: either to be assimilated into other cultures or to retreat ever further into a shrinking forest habitat. In the course of history, uncounted thousands of these original inhabitants of the wanni (dry monsoon forest) have been more or less absorbed into mainstream Sinhala society (as in the North Central and Uva provinces) or Tamil society (as on the East Coast). Today only a few remaining Wanniya-laeto still manage to preserve their cultural identity and traditional lifestyle despite relentless pressure from the surrounding dominant communities.

While the shy, retiring nature of the Wanniyalaeto has served to insulate them from the contaminating effects of contact with mainstream society, it has also effectively precluded their fair and adequate representation in the democratic decision-making process. Whenever a conflict of interests has arisen between the nomadic hunter-gatherer Wanniyalaeto community and the far larger dominant community of settled agriculturists and traders, the dominant community has invariably ignored the interests of the Wanniyalaeto.

Early Sinhala immigrants from North India were of the opinion that the forest-dwelling aboriginal were not human beings at all but wild jungle spirits (yakas) who were human in outward guise only. Such negative, stereotyped attitudes towards the island’s indigenous people persists up to the present day even in educated circles and has been a major stumbling block to the recognition of Wanniya-laeto self-respect, dignity, human rights, and cultural uniqueness. Hence, the Wanniyalaeto are widely assumed to be a backward, gullible people whose point of view may be conveniently ignored.

The vulnerable position of the Wanniyalaeto vis-a-vis mainstream society may be said to stem from two principal causes. One is that they have never received secure land tenure that recognizes their collective custodianship over traditional hunting and gathering ranges. The other reason is that they have never been consulted or represented in the decision-making process that affects their daily lives. Given the secure right to manage their traditional habitat according to their ways and given a voice to represent their collective aspirations within the framework of society at large, the Wanniyalaeto are more than capable of preserving both their endangered forest habitat and their ancestral culture for the benefit of all.

The Wanniya-laeto themselves operate within a radically different conceptual framework from that of the local administrators who wield power over Wanniyalaeto land and interests. For instance, the Wanniyalaeto do not entertain modern notions of real estate belonging to individuals, but believe that they and their ancestor-spirits belong to the forests of the Wanni which they inhabit and protect. Likewise, the concept of acreage is strange to them since they recognize only natural landmarks like hills, rivers, and villages. As a consequence of such cultural differences, the Wanniyalaeto have been repeatedly swindled out of their ancestral heritage by contrary interests anxious to seize control over Wanniya-laeto lands and forest resources. Such encroachment and economic exploitation has noticeably accelerated in the post-Independence era.

Similarly, modern observers have typically been blind to the basic facts about indigenous culture. For instance, Wanniyalaeto social structure is a matrilineal exogamous clan organization based on female line of descent.2 In simple terms, the Wanniyalaeto are a forest people who trace their ancestry through their mother’s line back to their mother-ancestor, the yaka-princess Kuveni.

This self-identification of the Wanniya-laeto differs radically from the definition of a ‘Vedda’ (‘hunter’) that was imposed upon them from outside with far-reaching social consequences. Hence, to colonial census-takers and other outsiders, a ‘Vedda’ was a primitive human-type of wild disheveled appearance, uncouth language and appearance, who resides in caves or wanders in the jungle, and who subsists by primitive means such as hunting with bow and arrows.

Thus, by these misleading criteria, the ‘Veddas’ (a term never used by the Wanniya-laeto themselves) were doomed to disappear in the course of time. Indeed, according to census records the Veddah population actually fell from 4,510 in 1921 to 2,361 in 1946 while since 1963 no separate count has been made, although a 1978 study identified six thousand Veddas in the Anuradhapura district alone. 3

This failure to recognize the Wanniya-laeto people’s own criteria of self-identification. Whether intentional or not, it has effectively accelerated their disappearance as a distinct culture and denied them representation in the democratic decision-making process.

As a result of pervasive social discrimination directed against the Wanniya-laeto, many of their people have adopted a survival strategy that includes taking Sinhala or Tamil names for themselves and their children, adopting the prevalent language, diet, dress, and lifestyle patterns and becoming, nominally at least, Buddhist or Hindu converts. And yet, because their matrilineal ancestry goes unnoticed and unrecognized by the dominant patrilineal society at large, the Wanniya-laeto have been able to preserve their social cohesion and cultural self-identification even while immersed within the outward trappings of cultures very much unlike their own.

A field study conducted in 1992 by a specialist in indigenous development policy from the International Labour Organisation succinctly summarized the plight of the Veddas (Wanniya-laeto) with respect to current development policy in Sri Lanka: According to the existing studies, the majority of the resettled Veddas are economically backward, socially isolated, and politically marginalised. The Veddas did not have the skills, means and knowledge needed to either adjust to the new situation (no knowledge of capital accumulation or savings, no familiarity with the monetary system of exchange, no long-term involvement in agriculture as a livelihood, lack of incentive for competitive tasks, etc.), or to cope with the other non-Vedda settlers. As a result, they are being exploited by the other settlers who have control over the local political institutions and economic opportunities; in several cases attempts to get the Veddas used to seasonal paddy cultivation have failed, thus worsening severely their livelihood since they do not resort any longer to hunting or food gathering. It has been pointed out that tribal peoples have suffered from depression and loss of confidence as a consequence of factors such as loss of land, loss of freedom of the forest and disappearance of ritual hunts as the causes of their demoralization. The situation has not changed substantially even after national authorities recognized the Veddas’ desire to preserve their cults and customs and to be resettled in close proximity to their traditional lands. 4

The same study traces the wholesale disruption brought upon Wanniyalaeto culture due to 20th-century development activities:

The drastic changes in the number, distribution and social organisation of the Veddas started in the 1930s and 1940s when large irrigation and colonization schemes in the Polonnaruwa and Mahiyangana regions were launched. These projects brought a massive influx of Sinhalese and Tamil colonists and a reduction of the forestland that was homeland to the Veddas. In the 1950s when the Gal Oya scheme was completed, access of the Veddas to their ancestral lands and their means of livelihood were eroded even more drastically.5

The Sri Lanka government’s concern for its indigenous people dates back to the early 1950s when a Vedda Welfare Committee was created as part of a Backward Communities Development Board. During this period, the prevalent philosophy of development regarded the disappearance of indigenous and tribal peoples as distinct societies as an irreversible and desirable process. Seen as backward and irrational, they were regarded as obstacles to national development and growth. Needless to say, such indigenous and tribal peoples as the Wanniyalaeto were not consulted for their views on the subject.

In recent years, however, the way of viewing the relationship between culture and development has undergone changes. Even during the 1960s and 70s, culture was considered to be irrelevant to the development process and much of the blame for failed development projects was attributed to resistance to modernization from affected traditional communities. Later, culture came to be regarded as inviolable and, as such, development was to be discouraged and enforced isolation was advocated. But this strategy also is inadequate to enable endangered cultures to cope with social change.

More recently, culture has come to be regarded both as a goal and as a framework within which to promote other development goals.6 This means that it is up to the affected people to decide how and to what extent to retain their cultural values and ways of life, and that any development initiative should bear these values in mind. Like all societies, indigenous cultures are subject to change, too.

Accelerated Development

In 1977 the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Scheme was launched, under which vast tracts of traditional Wanniyalaeto hunting lands were alienated for the proposed benefit of other communities. As usual, the offering of equitable compensation to the region’s displaced indigenous inhabitants was not even considered. Every major decision was taken either in far-off Colombo or in distant foreign capitals without consulting the region’s indigenous people.

Under the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Scheme, vast extents of forestland have been logged and inundated or earmarked for colonization. One last Wanniyalaeto hunting domain remained upon 145,450 acres of forest between the western chain of reservoirs and the Maduru Oya irrigation dam, but this too was on November 9th, 1983, declared to be the Maduru Oya National Park. It was intended as a habitat for displaced wildlife and as a protected catchment area: But under the terms of the Fauna and Flora Ordinance, “No person shall be entitled to enter any National Park, except for the purpose of observing the fauna and flora therein”, and “no animal shall be hunted, killed and taken and no plant shall be damaged, collected, or destroyed in a National Park.” Entry can be allowed only under “the authority and in accordance with the conditions of a permit issued by the prescribed officer on payment of the prescribed fee”, and only to allow the permit-holder to observe fauna and flora.

Consequently, the Wanniya-laeto, who had been occupational hunter- gatherers and custodians of the forest for uncounted millennia, were transformed overnight into game poachers and trespassers. Barriers, guards, and outposts were stationed along the park’s demarcated borders and the hapless Wanniyalaeto were evacuated to “rehabilitation” villages in Systems C and B of the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Scheme where they were to become rice cultivators (see Map of Mahaweli Development Scheme settlements). As one translocated Wanniyalaeto leader later observed, “The government took away our hunting tools and gave us mammoties to dig our own graves.”

The old Wanniyalaeto chieftain Uru Warige Tissagami (popularly known as Tissashamy) and his kinsfolk of Kotabakinni, however, refused to be evicted from the land of their ancestors. Officials considered him to be very obstinate and stubborn, for he would not budge an inch no matter how many emissaries came to “talk sense” to him. Finally the government had to concede that these seven families could remain as long as the old man lives. However, according to the 1987 Master Plan for Maduru Oya National Park, the day that aged chief Tissahamy expires, the rest his kinsfolk will have to evacuate the hamlet immediately.7 Knowing this, Tissahamy even refused to die (note: Tissahamy finally expired in June 1999 at the age of 96).

Wanniyalaeto leaders allege that since 1974 they have listened to official assurances that a sanctuary of 1,800-acre extent will be created for them to pursue their traditional way of life. Successive governments have repeated this pledge, but to date still no government has implemented its pledge. Even this modest figure (amounting to only one percent of the park’s area) was originally cited not as a sanctuary for all affected Wanniyalaeto, but only as a buffer zone to prohibit commercial logging activities around Tissahamy’s hamlet of Kotabakinni only.

In fact, the other affected hamlets cannot possibly be included in a sanctuary of this size, which is sufficient to sustain a few families by their traditional means of livelihood. But the 1,8OO-acre figure has remained to be seized upon by officials and even, years later, by Tissahamy’s attorney, resulting in further tensions and misunderstandings.

However disadvantaged the island’s indigenous forest-dwellers may appear to be in the eyes of modern-educated observers, nevertheless their sense of honour, justice, and fair play is very keen. Despite centuries of injustice and exploitation by economic predators from outside communities, even to this day the Wanniyalaeto people remain so gentle and patient towards younger cultures that, although they are proficient hunters, they have never been known to raise a weapon in anger, to commit theft or fraud out of greed, or even to raise their voice toward outsiders, let alone to speak any untruth for personal gain. Indeed, these are precisely the elements of their cultural heritage that the Wanniyalaeto are most anxious to preserve for future generations. Colonised Wanniyalaeto are deeply dismayed by the corruption of their culture caused by forced assimilation into a modern society which they regard, justifiably, with utter contempt.

Human Rights

In the absence of any provision for direct representation of indigenous interests in official decision-making, the Wanniyalaeto have explored other potential avenues to achieve justice, including a court system that is completely alien to their own tradition of justice. Going still further, chief Tissagami and other Wanniyalaeto leaders have been granted sympathetic hearings by Presidents Jayewardena and Premadasa respectively and by other high-ranking officials who have promised to rectify injustices, but resistance to change within the government bureaucracy has effectively stifled every high-level initiative designed to respect Wanniyalaeto aspirations.

Over the years, scientific interest in the millennia-old Wanniya-laeto culture has helped to bring their plight to international notice. In particular, one Swedish cultural anthropologist, Dr. Wiveca Stegeborn, has been closely associated with the Wanniyalaeto community of Dambana since 1977, even to the extent of learning their language and living among them as one of their people. With her professional training and close familiarity with the kinds of problems that the Wanniyalaeto have faced in recent years, Dr. Stegeborn has played an invaluable, if little-appreciated, role in garnering international sympathy and support for the Wanniyalaeto community.

With Dr. Stegeborn serving as their intermediary and patron, the Wanniyalaeto were invited to come to Geneva in 1985 to submit testimony before the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations Commission on Human Rights, Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities. But the three Wanniyalaeto delegates were unable to attend because officials of the Sri Lanka Government’s Department of Immigration and Emigration refused to issue passports to them. One of the reasons offered for the refusal of passports was that the Wanniyalaeto were “not real Sri Lankans”.8 Subsequently, Dr. Stegeborn was declared persona non grata, further obstructing efforts to redress social injustice.

Wanniyalaeto people say that they are still prohibited from pursuing their ancestral livelihood and face harassment or arrest by wildlife officials if they are caught ‘trespassing’ outside of their tiny enclaves. Tribal leaders accuse the armed forest officers of intimidation and allege that only recently the same officers were responsible for the shooting deaths of three Wanniyalaeto clansmen.9 To date, however, no investigation of the incident has been made.

Wanniyalaeto Sanctuary

On June 16th, 1990, President Premadasa and other high-level officials met in Kandy with a delegation of Wanniyalaeto leaders including chief Tissahamy to discuss longstanding grievances and measures required to address these grievances. Following the meeting, President Premadasa ordered prompt steps to be taken to reverse years of official injustice towards the indigenous community. Three days later, the President’s Minister for Lands, Irrigation and Mahaweli Development, Mr. P. Dayaratna, recommended and later received Cabinet approval for the following two-fold course of action:

(i) Demarcate an area of approximately 1500 acres (covering Kotabakiniya, Keragoda, Buluganhadena and Kandeganwila villages), from the area gazetted as the Maduru Oya National Park, and declare this area as a Sanctuary under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance.

(ii) Take specific measures to protect and nurture ‘Vedda Wanni-etto’ culture and establish a Trust or a Board for this purpose under the chairmanship of the Director of Wildlife Conservation with representation from the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and other relevant state agencies and non-governmental organizations. 10

Under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance, all traditional Wanniyalaeto occupations including hunting, honey-gathering and chena cultivation are prohibited within national parks, but ‘limited human activities’ are permitted within other areas defined as ‘sanctuaries’. However, the four aforementioned Wanniyalaeto hamlets cannot be encompassed within 1500 acres only, nor can 1500 acres sustain more than a few families living by hunting and gathering supplemented by shifting cultivation. Moreover, no provision is included to accommodate families of evacuees who wish to return to their former habitat.

Wannietto Trust

As of early 1993, section (i) of the 1990 Cabinet order has yet to be implemented. Regarding section (ii), sixteen months passed before officials from other concerned ministries and NGOs (including Cultural Survival) were invited to serve on the Board of the proposed Wannietto Trust, and another five months passed before the first meeting was actually held in April, 1992. In four meetings to date, the Trust has accomplished very little in concrete terms “to protect and nurture” Wanniyalaeto culture.

Its meeting of March 4th, 1993, appeared to have marked a watershed, however, with the long-overdue nomination of the first (university-educated) Wanniyalaeto representative to join as a full member of the Board and with the recognition at long last among Board members of the urgent need to implement section (i) of the 1990 Cabinet order. But first officials must resolve ambiguities regarding the boundaries of the Wanniyalaeto sanctuary.

The Wannietto Trust has been further hamstrung by the lack of any office facility and complete absence of any government funding, even to photocopy documents or to hire a paid secretary, fueling speculation that the Trust was created as a mere political eyewash. Since its creation, the Trust has relied almost entirely upon the NGO Cultural Survival of Sri Lanka to provide it with supporting documentation and liaison with Wanniyalaeto leaders and with concerned international agencies like the International Labour Organisation and others. This dependency has also put strains upon Cultural Survival’s resources.

The present context of 1993 as the International Year for the World’s Indigenous People has provided an opportunity to draw greater public and official notice to the plight of the Wanniyalaeto, but so far its effect has been cosmetic only. Since creation of the Maduru Oya National Park, the living standards, nutrition and morale of the Wanniyalaeto have markedly deteriorated. Meanwhile, plans are afoot to open the park not to Wanniyalaeto but to tourists willing to pay stiff entry fees. Tour operators have already been driving their clients up to the very doorstep of Wanniyalaeto hamlets to entertain them with sights of ‘the last Veddas’, even against the inhabitants’ expressed wish to the contrary. Further violations of Wanniyalaeto cultural norms will surely hasten the final demise of their ancient culture.

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka has been elected to the UN Commission on Sustainable Development that was established “to oversee, coordinate, monitor, review and report on the implementation of Agenda 21”, but in Sri Lanka little is being done to ratify — let alone implement — international protocols such as Agenda 21 and ILO Convention No.169 that concern the rights of indigenous people like the Wanniyalaeto. Still no mechanism exists for regular consultation between Wanniyalaeto leaders and government officials, while many privately fear that the government is only waiting for old chief Tissahamy to expire before plowing through with an agenda more attractive to private interests.

References

- “Pre-Anuradhapura civilisation discovered”, Colombo: The Sunday Island, 3 January 1993.

- Seligmann, C.G. “Notes on Recent Work Among the Veddas”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon), Vol. XXI No. 61 (1908), p. 74.

- Brown, J. Veddha Villages of Anuradhapura: The Anthropological History of a Community in Sri Lanka (1978).

- Tomei, Manuela. “A Plan for the Cultural Preservation and Development of the Veddhas” (1992), pp. 10-11.

- Tomei, p. 11.

- Tomei, p. 11-13.

- Master Plan, Maduru Oya National Park. Sri Lanka Ministry of State, Department of Wildlife Conservation, October 1985, revised June, 1987, p. 40.

- Immigration Officer (anonymous), Colombo: personal communication to W. Stegeborn, July 1985.

- “Veddhas Want to Return to their Homelands in the Jungle” Colombo: The Island, 14 May 1992.

- Dayaratna, P. “Establishment of a Sanctuary in 1500 acres of land within the Maduru Oya National Park for Uruwarige Tissahamy and the Veddha clan to pursue their traditional way of life”. (note to Sri Lankan Cabinet) 19 June 1990.

Maps

- Map A: Traditional Vedda settlements in Sri Lanka

- Map B: Mahaweli Vedda resettlement areas

- Map C: Vedda hamlets in Maduru Oya National Park

Text and maps from report submitted to Sri Lanka’s National Committee for the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People in 1994 by Cultural Survival of Sri Lanka. For more information contact the author at: kataragama@gmail.com.